The conference “100 Shades of the EU: The Political Economy of the EU Peripheries Between Pandemic and War” expanded on the ongoing work by transform! europe on EU peripheries. It brought together academic researchers and trade unionists from across Europe. Here is a summary of the discussions held during the sessions.

The April conference aimed at broadening the discussions around the comparative study Hundred Shades of the EU — Mapping the Political Economy of the EU Peripheries published by transform! europe in 2022 together with a wide range of actors.

The two-day conference was coorganised by transform! europe in cooperation with the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung, CGIL Trieste (Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro), and CSI Nord EST / MSS Severovzhod (Consiglio Sindacale Interregionale Friuli Venezia Giulia /Slovenia – Medregijski sindikalni svet Furlanija-Julijska Krajina/Slovenija).

Held in the italian port city of Trieste, the conference was opened by Robert Treu, president of IRTUCs Friuli Venezia Giulia/Slovenia CGIL and gave the floor to several trade unionists from the port industry sector as well as to several academic researchers from all parts of the European Union.

The discussions were organised in eight thematic sessions:

- Opening by Robert Treu (IRTUCs/CGIL)

- Presentation of the study

- The political economy in central eastern europe in times of crisis

- Welfare state, green transition and growth: what alternatives?

- Peripheral growth models

- The position of labour and wages

- Institutions, geographies and inequalities

- Shipbuilding industry: labour’s right and industrial policy

- The international port of trieste: public government in value chains

You can read below our report on each of these sessions, synthesized by Tatiana Moutinho and based on the notes by Tatiana Moutinho, Roland Kulke and Piera Muccigrosso.

OPENING / SESSION 1 | 3 APRIL 10:15–12:00

VALENTINA PETROVIĆ, GIUSEPPE CELI, VERONIKA SUŠOVÁ-SALMINEN, TATIANA MOUTINHO

VALENTINA PETROVIĆ, GIUSEPPE CELI, VERONIKA SUŠOVÁ-SALMINEN, TATIANA MOUTINHO

SESSION 1 — PRESENTATION OF THE STUDY BY THE AUTHORS

Opening Keynote

by Robert Treu, President of IRTUCs Friuli Venezia Giulia/Slovenia CGIL

Robert Treu opened the Trieste Conference by highlighting several issues and ideas:

- He first evoked the issue of port management, which remains public in Italy but not necessarily across Europe.

- Treu also stressed the fundamental role of trade unions in fighting for the rights and opportunities of cross-border workers.

- The economic inequalities in wages and workers rights in Central and Eastern European countries impose challenges in guaranteeing mobility to peripheral countries based on transparent rules and recognised workers’ rights.

- We need a binding directive for the EU social pillar, not just a recommendation.

- We need political developments in the EU that go beyond the monetary and economic policies: a more cooperative and less competitive EU that can do away with nationalism.

Economic Models of EU peripheries and Global Interactions

by Giuseppe Celi, Associated Professor of Economics, University of Foggia, Italy

Giuseppe Celi emphasized the fact that the socio-economic peripheries, while sharing a fate of dependency, are differentiated in many ways given their differently structured economies or economic models, which arise from different historical contexts.

Southern EU countries

- The crisis of the 1970s stopped or slowed down the industrialisation process, while the ensuing neoliberalisation period led the financialisation of the economy and the hypertrophisation of the service sector, resulting in a persistent incompleteness of the production matrix.

- The current economic model of Southern countries is a debt-financed consumption-led growth in absence of a complete productive base model. It fails to achieve economic and social convergence in the EU.

- Competition from Central and Eastern peripheral countries further contributes to weaken the production basis in Southern countries.

- Since the 90’s a divergent path is observed in Southern countries whereas some convergence is observed for (some) of the Central and Eastern ones.

Central Eastern countries

- Foreign direct investments are the main source of economic growth and development, which represents a form economic and social dependence.

- Within Central Eastern countries different important economic differences coexist – Baltic countries depend on FIRE (finance, insurance and real estate), Bulgaria and Croatia depend on tourism and Visegrad countries depend on industry but linked to foreign capital.

Global interactions and trade networks

- At the global level, major changes have been occurring since 2000. They were dictated by three dramatic developments: the euro’s inception, the 2008 financial crisis and the “Trump effect”.

- It is important to analyse both intermediate and final goods – international fragmentation of labour and production, also observed both in core and peripheral countries.

- The automotive sector is paradigmatic in the analysis of the development of global value chains (GVCs) in the EU.

- The share of the Southern member states in German exports has remained low and unchanged since 2005, whereas Central Eastern Europe could well expand its position. The difference between the core and the periphery is also influenced by the fiscal leeway available to the states.

Perspectives in the new geo-economic context

- The pandemic and the war in Ukraine are leading to destabilisation of GVCs with asymmetric impacts.

- The recent developments stopped hyper-globalisation, exposed the vulnerability of the Russian energy dependence for core and peripheral countries, reshuffling the traditional core-periphery division.

- These put into question the German export-led growth model and the obsession of competiveness.

- The problem is that a polarized Europe is vulnerable.

- The expansion of internal EU demand can be a sustainable solution.

The Political Manifestations of the Core-Periphery Divide

by Valentina Petrović, Post-doctoral researcher, Department of Sociology, University of Zurich, Switzerland

Valentina Petrović outlined the different outcomes for the Left in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis in EU peripheries:

- A stronger left in Southern countries (with the exception of Italy), stronger (often illiberal) right in CEE countries.

- Cleavages between Southern and Central Eastern European (CEE) countries have historical roots linked to the nation-state building processes.

- Strategic question for the Left: transnational cooperation across Southern and CEE countries.

Potential of coalition building: material and perception obstacles do exist

- Concrete obstacles: a split between euro and non-euro member states; migration and fiscal policies/space are two converging “top priorities” for both Southern and CEE countries.

- Perception obstacles: peripheral elites “imagine” more core allies than really exist; peripheral countries search more coalition partners amongst regional peers; peripheral countries tend to perceive potential alliance partners in core countries but not vice-versa; Spain, Italy and Czech Republic are perceived as potential partners for both core and other peripheral countries.

- Ephemeral peripheral countries coalition events (EuroMed9 and Friends of Cohesion Summit) – will these last and provide some sort of answer.

More transnational coalition potential between the two peripheries than meets the eye

- Political representation in EU bodies is unbalanced, with Central Eastern European countries underrepresented in the leadership when taking into account their population size and member state share.

The Unbearable Lightness of Imitation. Mimicry & Dependency in Central Eastern & Southern Europe

by Veronika Sušová-Salminen, Independent Researcher, Czech Republic/Finland

In her lecture, Veronika Sušová-Salminen further deepened the questions of international and transnational dependency structures. Her lecture focused on the cultural side of the dependency differences in the capitalist world system:

- The domination and dependencies of the base structure of capitalism find their partial counterpart in the superstructure.

- The literature, such as the postcolonial studies, has worked out how value systems on the periphery are put under pressure and sometimes “remotely controlled” by the material and ideological pressure or “models” of the centre (media, educational systems).

- The centre thus gains intellectual authority with regard to lifestyle, to the formation of future plans for one’s own national society.

- Catch-up development often remains the only purported option. Mimicry is thus a cultural phenomenon of the periphery.

- The question of resistance and the autonomous orientation of the national periphery arises here dramatically.

— Discussion on Session 1 —

Notes from the general discussion

- Peripheries coalition building from the social movements side (migration, peace…) rather than from State or parties.

- From an economic perspective Southern and Eastern peripheries lack capital and knowledge.

- Eastern cheap labour and capital from the core is of the interest of the peripheral elites; elites competition within and between peripheries is a fact; necessity of a EU-based solidarity rather than competition.

- Re-evaluation of the role of the State vis à vis the EU.

- Necessity of a reindustrialisation economic model – ecological transition in both peripheries can be an opportunity.

- Dialogue building between Southern and Eastern migration.

- Bypass the core and work together between peripheries; labour movements in core countries are allies.

- Poland has risen to a contender of political hegemony in questions of peace and war without realising a comparable economic gain.

SESSION 2 | 3 APRIL 13:00–14:30

Attila Antal, Veronika Sušová-Salminen, Gavin Rae

SESSION 2 — THE POLITICAL ECONOMY IN CENTRAL EASTERN EUROPE IN TIMES OF CRISIS

The Political Economy of Emergency Governance in Hungary

by Attila Antal, Eötvös Loránd University Faculty of Law Institute of Political Science, Budapest, Hungary

Attila Antal discussed the “very actual and very sad story” of the current government in Hungary: the permanent state of exception seems to be the new governing model.

- Covid-19 pandemic further increased the authoritarian drift of Orban’s government – authoritarian crisis management based on never-ending governance of exception.

- Exceptional governance fits the neoliberalisation process.

- Refugee crisis as a “tailored state of exception”: 2015 as a tipping point in terms of exceptionality — the year of “biopolitical hate campaign” vis à vis migrants and refugees and the creation of inner enemies (Soros, ONGs, “Brussels”).

- The overlap of (state of) exceptions: the creation of “sequential links” between migration, COVID-19, the health crisis emergency and the armed conflict and the humanitarian crisis

- Political economy of the state of exception: Orban’s regime class politics (socially formed and politically coerced class compromise), neoliberalisation of Hungarian economy and regulations (destruction of workers’ rights, trade unions, attack on the right to strike, new Labour Code); strengthening of Eastern relations (Hungary as EU entry gate for Russia and China); neoliberalisation of public services (privatisation waves, abolition of civil servants status).

- Class alliances resembling fascist tendencies: compromise between petite bourgeoisie and big capital enforced by the government.

Military Keynesianism: Poland’s New Macroeconomic Policy on the Edge of War

by Gavin Rae, Fundacja Naprzód, Poland

Gavin Rae discussed the question of whether Poland can use the massive rearmament that the right-wing government is planning to escape from the economic crisis in which Poland, like other countries, is stuck.

- Since Poland’s accession to the EU, GDP has caught up with the core but the country remains a peripherical economy. Increasing investment in the military industry is used as a means to become a political economic and military power but Poland is facing an economic downturn.

- The paper’s even broader question was whether this might be an example à la Kalecki’s “Military Keynesianism”. This concept of the time after the Second World War said that Western countries succeeded in raising their economies to a higher growth path by investing massive capital in armaments that were only partially used, i.e. “dead assets” were created. But since people were paid and machines were produced, there was a large increase in demand for the entire economy at that time, which allowed wages to rise in general and unemployment to be eliminated.

- Gavin Rae shows that the armament strategy, which is in any case politically dubious, is of no use economically either. Only 20% of defence spending will create demand in Poland’s economy. 80% goes to the USA and South Korea.

- So the Polish right-wing government does not help the national economy, but rather runs a generous development aid program for the military-industrial complexes of South Korea and the USA.

— Discussion on Session 2 —

Notes from the general discussion

- Crosscutting class support to both regimes: no real opposition or alternative exists.

- The prolongation of the war in Ukraine is of interest to military corporations, and particularly the US, without any autonomous European politics.

- Necessity of a European security agreement.

SESSION 3 | 3 APRIL 14:45-16:30 Nadia Garbellini, Giuseppe Celi, Annamaria Simonazzi, Giacomo Cucignatto

Nadia Garbellini, Giuseppe Celi, Annamaria Simonazzi, Giacomo Cucignatto

SESSION 3 — WELFARE STATE, GREEN TRANSITION AND GROWTH: WHAT ALTERNATIVES?

Social Investment as an Engine of Growth and Innovation: the Case of Long Term Care

by Annamaria Simonazzi, Professor of Economics at Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Annamaria Simonazzi opened her contribution by saying that her paper could also have had the title “Care-Keynesianism” and would fit perfectly to the preceding discussion on a supposed Military Keynesianism. However, she would use the time to talk about another bomb: the demographic bomb.

- Right now, our societies would go from an average of 1.7% of GDP expenditure on long-term care (LTC) to 2.5% by 2050. The composition of our societies will change so that by 2070 there will be only two workers for every person over 65. The number of people over 80 will increase from the current 9.9% to 25% in 2070. The financing issue will not only affect the budgets of the public sector, with long-term care reforms currently underway in many countries, but above all the families (informal carers are responsible for 80% of total care work, 75% of whom are women).

- The question(s) raised by Simonazzi were framed by the subtitle of her paper: can social investment be an engine for growth and innovation? Can we achieve a “Smart LTC” in the sense of “New Brain & New Hands”? Can tele-assistance, telemedicine, smart homes, assistive technologies – sensors, robots, wearable devices, platforms connecting users and care providers and big data be of help? What about the future development of AI?

- “Smart” long-term-care could be envisioned as an engine for growth: digital transformation of healthcare (long-term care included) is creating not only new market segments, but also small companies and start-up businesses.

- The mapping of the industrial Internet of Things (IoT) in Europe revealed that most products have few specific tasks and lack standards communication protocols that would account for better efficiency and effectiveness.

- In addition, big oligopolies of the platform economy are already investing heavily in the digital health economy, because they sense big profit opportunities here.

- We are currently witnessing a blurring in the boundaries between health care and IoT, which raises new social, economic and political problems. The latter, in turn, are not determined in Europe, but by international trade agreements.

- EU industrial policy has devoted substantial amounts of funding to LTC innovative technologies but still relies on the market to create demand. The European Commission recommendation of 2022 on access to affordable high-quality long-term care considers mobilising funds to promote national reforms and social innovation for long-term care.

- The introduction of innovative technologies in the long-term care could lead to better care and better jobs (case of Japan).

Ecological Transition or Energy Revolution for the EU? A Reconsideration in the Aftermath of the War

by Giacomo Cucignatto, Postdoc Researcher, Department of Economics and Law, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Giacomo Cucignatto started his presentation by pointing out the fact, often suppressed in the West, that the West is responsible for the ongoing climate catastrophe because of the historical climate debt. At the heart of the ecological transition is the energy sector.

- Importantly, Cucignatto further dispelled the myth of a supposedly successful ongoing shift towards renewable energies (RE). Fossil fuels completely dominate the electricity production worldwide, and 84% of the world’s energy is based on burning fossil fuels such as oil, gas, and coal.

- It was also noted that the necessary energy transition cannot be achieved in a geopolitical scenario of competition and conflict – the goal of net-zero emissions is not possible to reach without cooperation with China, India, and the rest of the world. While the US and the EU are increasingly collaborating on liquified natural gas (LNG), China clearly dominates global investment in RE with 75% of global spending in 2018-2022.

- In addition, critical raw materials are essential for both green transition and digitalisation and this represents a strong vulnerability for the EU. The case is even worse when it comes to rare earth elements (EU needs are 98% dependent on China).

- A 2023 McKinsey report shows that, to achieve Net-Zero by 2030 we need a six-fold increase in wind energy, a fourteen-fold increase in solar photovoltaic technologies, fourteen times as many e-cars, requiring 200 times as much hydrogen production capacity, and a hundred-fold increase in carbon capture and storage capacity globally.

- The distribution of emissions all over the world is extremely inequal, with 5% of the richest countries responsible for a share of 37% and the 10% richest contributing to 46% of emissions’ growth.

- The class dynamics within the ecological transition was highlighted/deepened by the pandemic and war, with the profits on the energy and mining sectors more than doubling in profits, a dynamic that can be traced also to downstream sectors. Even the European Central Bank acknowledges the profits’ contribution to the inflation trend.

- To which extent can the EU new industrial strategy accomplish the task of energy transformation (and ecological transition)? This question was also addressed in this presentation. Although the past was marked by the supremacy of horizontal and market-oriented industrial policies with no room for vertical interventions or state-aid rules, recent initiatives have targetted “strategic autonomy” and “technological sovereignty” in key sectors, which, for several reasons, still fail short.

- Giacomo Cucignatto issued the following demands at the end: To enable ecological transformation, we need a structural transformation of the mode of production with a strong emphasis on class relations and labour interests. This calls for a universal job guarantee for workers in hard-to-abate sectors. Furthermore, the planning and investment capacities of state administrations must be expanded, which would mean a substantial increase in the number of public employees.

Industrial policy from a left-wing perspective

by Nadia Garbellini, Professor, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia – Italy

Nadia Garbellini started by defining what an industrial policy is from a left-wing perspective.

She first focused on the problem of the fiscal rules.

- What we know about the current plans for a reform of the Stability and Growth Pact is that they are not up to the task and we need a much more radical reform of the European fiscal rules to have the fiscal room for manoeuvre for the necessary investments. Despite all this, is there any space for developing a left-oriented industrial policy?

- The Next Generation EU fund (NGEU) with the 800 bn euros as common debt is a good start but still nothing more than essentially a transfer of public money to the private business sector, which can spend it mostly without any social conditionalities. Besides, there is also no common plan linked to the NGEU as the plans only occur at the national, not European, level.

- China is that strong in the sectors we evoked because China’s long-term development plans are specific and focused.

Industrial policy must be performed by the public sector.

- We must bear in mind that direct action by member states is possible. National Development Banks, like KfW (Germany), Cassa Depositi e Presti (Italy) or ICO (Spain) are government-owned financial institutions that stand outside the national budgets and are therefore not affected by the Maastricht criteria.

- States can use “inhouse production” with state-owned enterprises (SOE) in the realm of “Services of General Economic Interests” (SGEI) like water, transport, energy, waste management and telecommunications.

- It is also important to state that there exists no fixed list of these services granting special room for manoeuvre to member states under EU competition law.

- That means it would be possible for left governments to enlarge the definition of what is considered a SGEI – and hence enlarge the room for manoeuvre for national economic policies.

- Nadia Garbellini stated that “we need to abandon the idea that states aren’t allowed and can’t plan” because supply management of SGEI is no more, no less than centralisation of planning.

Fighting inflation

- Her political demand at the end was that we need publicly administered price caps to stop the inflation.

— Discussion on Session 3 —

Notes from the general discussion

- The financialisation of the elderly care sector was emphasised as the next frontier of financial encroachment, following the housing sector, which has already been taken over by finance.

- The question was also raised of long-term care AI and robotisation as paths towards a rather dystopian future, destroying labour whilst intensifying performance.

- As a further concern it was pointed out that digitalisation expenditure in health sector could pave the way for (deepened) healthcare privatisation.

- We also discussed the issue of how to reconcile price control with the need to lower energy consumption.

- The question was raised how the necessary and fast dissemination of the production of renewable energies can be balanced with the fact that we do not have enough resources such as rare earths for all that we plan or wish for.

SESSION 4 | 3 APRIL 16:45–17:45

Marius Kalanta, Gabriel Sakellaridis

SESSION 4 — PERIPHERAL GROWTH MODELS

Growth Models, International Investment Positions and Financing Patterns: The South-European Road to the Crisis and its Aftermath

by Gabriel Sakellaridis, Eteron Institute for Research and Social Change, Athens, Greece

Gabriel Sakellaridis discussed of whether a distinctive Mediterranean growth model does exist and where does it come from (domestic versus external factors).

- Four growth models can be identified in Europe: consumption/debt-led growth model (UK), export-led model (Germany), balanced growth model (Sweden) and the “stagnationist” model (Italy).

- In South Europe economies, prior to the financial crisis a consumption-led growth model fuelled by credit and debt was being followed, with gross fixed capital formation centred on low productivity and non-trade sectors (mainly construction and real estate).

- After the 2008 crisis, these economies turned into a (weak and unsustainable) export-led growth model marked by low export sector participation in GDP, a focus on intermediate goods and low-value added services (especially tourism).

- Last but not least, we see low R&D and technical composition while low taxation is a problem, especially in Italy.

- A huge challenge is the lack of a lender of last resort in the Eurozone.

- But we need to broaden the perspective. The current international monetary system is centred on the US, with the Eurozone itself a part of the global periphery of the world financial system, with different layers depending the advancements by European banks.

- Still, to understand the economic crisis in the Southern EU in the 2010s we need to state the fact that strong push factors, not only pull factors, caused the crisis.

- Before the crisis, although Southern countries were not guiltness, we had a situation of great money supply in the centre, which searched for investment opportunities, thus offering extremely low interest rates for creditors lending to the South.

- These huge flows of finance towards non-competitive economies were the problem, as it was from now on impossible to devalue in order to rebalance the different economies.

Middle-Income Trap and Diverging Growth Models in the Baltic States

by Marius Kalanta, Postdoctoral fellow, Institute of International Relations and Political Science, Vilnius University, Lithuania

Marius Kalanta discussed the questions whether the Baltic States face the risks of the “middle-income trap” (MIT) on the one hand and, on the other hand, how the growth models of Estonia and Lithuania can achieve success.

- The so-called “middle-income trap” thesis assumes that while many countries around the world manage to rise from poverty to emerging market status, they fail to make the leap to full industrialised state status.

- Kalanta’s careful analysis shows that, despite the difficulties, Baltic states have opportunities to escape the middle-income trap.

- His research makes an exciting case for the question of how peripheries are doing in general, as he showed how different countries can develop through their own choice of internal strategies – the cases of Estonia and Lithuania.

- The core explanatory factors of the differences between both countries go back to the 1990s. The political elite in Estonia was strictly pro-Western and tried to take an anti-Russian course with Russia being narratively identified with the old industrial society.

- By implication, it was natural to equate “the West” with a post-industrial digital economy. This vision served to mobilize the population nationwide.

- Finance capital was the vehicle of digitalisation. In the post-2008 financial crisis, finance capital in Estonia managed to maintain its strong position within the hegemonic social bloc, while in Lithuania finance capital was displaced in favour of the interests of industrial capital.

- In Estonia, therefore, the material basis (financial capital) of political decisions in favour of rapid digitilisation remained intact.

- Estonia’s growth model follows the idea of leapfrogging the state of industrial development by investing immediately in upcoming but not fully developed technologies and becoming economically competitive – yet the technological development remains premature and incapable to deliver products comparable to those of advanced economies.

- It was further noted that the old, industrialised countries (e.g. Germany) do not have a comparative cost advantage.

- So far, this va banque game seems to have worked. What we see is empirical evidence that political factors such as strategic objectives can play a significant role in determining a country’s economic status. So, there could exist auto-centric development opportunities for countries in the current periphery.

— Discussion on Session 4 —

General notes from the discussion

- The discussion focussed on the existing banking union as well as the debate on the capital union.

- The question of internal national room for manoeuvre vs external structural restriction of peripheral societies to develop according to their own visions was also further deepened.

SESSION 5 | 4 APRIL 10:00–11:15

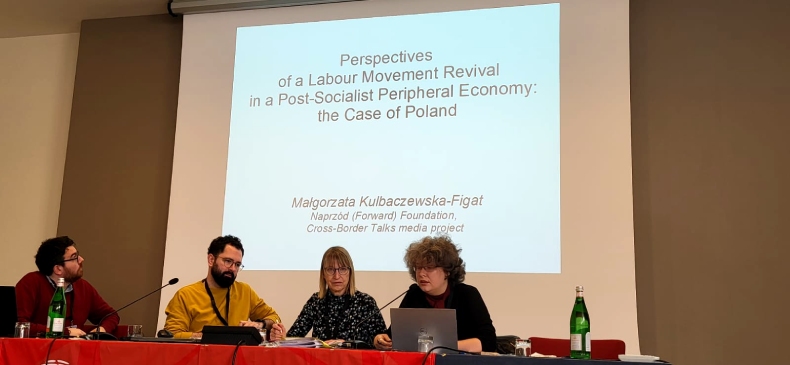

Vincenzo Maccarrone, vLADIMIR Simović, Cornelia Hildebrandt, Małgorzata Kulbaczewska-Figat

SESSION 5 — THE POSITION OF LABOUR AND WAGES

European Periphery Outside of the EU: the Case of Garment and Shoe Industry in Serbia

Vladimir Simović, CPE – Centar Za Politikie Emancipacije, Belgrade, Serbia

Vladimir Simović spoke about the interdependence of the Serbian growth model and the national wage regime:

Low wages and an anti-trade union policy are part of the official national development plan and, thus, internationally promoted (for example in advertisements on CNN).

- “Lohn-system” is a special EU trade system of manufacturing and trading garments to support EU capital and providing it with a cheap “hinterland”. In the case of Serbia (and other Balkan countries) almost all raw materials for garment (textile, clothing, leather and footwear) production are imported and the products are re-exported as “semi-finished products” (packaging and labelling are done in other countries, such as Italy, prior to selling on the European markets).

- The problem of a minimum wage in Serbia: since the minimum wage represents 60% of the national full-time gross median wage, “60% as minimum wage of nothing is still nothing” – the average wage is of 670€ with less than 10% of workers earning more than 1000€/month.

- What the Europe Floor Wage, a civil society alliance, is demanding is a “cross-border living wage”. Workers need both: a living wage and a transnational coordination of these wages to stop the competition, which is actually a race to the bottom.

- A true living wage, which would enable the common people to pay for education, health, transport, food and housing, would look much different to the current situation. The minimum wages in Serbia do currently cover only 25 – 33% of the living wages. The wages are so low in the Balkan region that in Macedonia an average paid worker needs 40 minutes to earn enough money to buy one litre of milk (33 minutes in Serbia, 6.6 minutes in Germany).

- The automotive sector is of fundamental importance for the region. The local firms are included at the lowest level of the international value chains of the French and German car industry.

- In Serbia there are 15 free trade zones, which support every newly created job with 50.000€, extreme tax breaks and the possibility to basically repatriate all profit made in Serbia to the European central economies.

- “It is basically wild west” what we see regarding capitalism in the Balkan region. We recognize an “atmosphere of fear, [where] people are being afraid of raising their voices”. Profits are distributed highly unevenly along the value chains, with the lowest being the workers’ pay.

Perspectives of a Labour Movement Revival in a Post-Socialist Peripheral Economy: the Case of Poland

by Małgorzata Kulbaczewska-Figat, Journalist, Fundacja Naprzód, Cross-Border Talks editor-in-chief, Poland

Małgorzata Kulbacczewska-Figat discussed the possibility of a revival of trade unions and a stronger labour movement in Poland.

- After the reintroduction of capitalism in the 1990s trade unions were severely weakened, and confined to the public sector, local and government institutions, and big corporations/enterprises.

- This trend has been slowly changing in the last years due to companies’ relocation from the West towards Eastern European countries, also with new generations of workers entering the labour market.

- Although in the years 2017 to 2019 people became more sceptical vis-à-vis trade unions, the trend is of growing acceptance towards a bigger role of the labour movement. In a public poll the majority of the people clearly stated that the role for the trade unions was “too little”.

We have been witnessing two interesting developments recently.

- First: in the years 2019 to 2022 workers organised several strikes in multinational enterprises in Poland.

- And secondly the younger generation of 20-year-olds now entering the workforce no longer believes in the promise of free capitalism. They are far more willing to take a radical stance in labour disputes, and 80% of the 18–24-year-old Polish workers have a positive view on trade unions and workers movement.

- An important factor in the new relative strength of the labour movement is the reindustrialisation of Poland through Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs). Of course, the valorisation of these investments for the benefit of Polish workers still leaves much to be desired. But it shows that countries on the periphery can achieve reindustrialisation, which can then contribute to the strengthening of the trade unions.

- An internal obstacle still hinders a more successful class struggle of the workers: the big trade union federations often remain “bureaucratised” and hence reluctant to radical actions.

- This attitude is supported by a clear anti-trade union legislation.

Currently the radical workers’ movement faces three challenges.

- The first is the arrival in Poland of millions of Ukrainian refugees, who are pushed into low wage sectors. Missing public support, they are forced to work for low wages.

- Platform work is an additional challenge for unionizing attempts, but the underfinanced labour control is also not helpful here.

- And last but not least, the cost-of-living crisis is currently threatening to erode the strike movements of recent years – the large real wage losses of the past two years may cause workers to withdraw in frustration. The rise in minimum wage and partial social reforms by the conservative government has helped workers, but these effects are now greatly reduced by inflation and cost of living crisis, which may open new windows for workers’ protests and demands.

Common Pressures and Uneven Trajectories: Assessing Ten Years of European Governance Interventions on Irish and Italian Wage Policy

by Vincenzo Maccarrone, Marie Curie Post-Doctoral Fellow, Scuola Normale Superiore, Florence, Italy

- Vincenzo Maccarrone started by addressing the changing impact of EU integration in national industrial relations, marked by the 2008 financial crisis. Until the global financial crisis (GFC), strong albeit indirect commodifying pressures provided by the European Single Market and Monetary Union were put in place and, simultaneously, direct decommodifying directives outside the core of industrial relations (wages, collective bargaining, right to strike) existed; since the GFC, new economic governance regimes introduced direct commodifying interventions, while decommodifying directives (for example, the directive on adequate minimum wages) have been targetting the core of industrial relations.

- The trajectories of change in industrial relations derive from common neoliberal transformation of industrial relations through the European integration process and the uneven effect of internationalisation and EU integration.

- Throughout EU countries, variegated forms of neoliberalism have intensified uneven developments of regulatory forms leading to variegated Europeanisation. When it comes to wage relations, the case addressed by Maccarrone, variegation is of dual character, occurring both at the EU and national levels.

- The research presented in this paper addressed different dimensions of industrial relations (wage policy, collective bargaining, and employment protection legislation) in two country cases: Ireland and Italy. In the Irish case, measures fully complying with Monetary Union lines and attacking national minimum wage (NMW) and collective bargaining (CB) were put in place, with partial reversion of the reduction on minimum wages. In the case of Italy, where minimum wage does not exist, measures target collective bargaining and employment protection legislation, some of them partially reverted. So, in both cases, similar prescriptions regarding collective bargaining were implemented whereas no prescriptions regarding employment protection legislation (EPL) were made for Ireland nor regarding minimum wages in the Italian case.

- In his concluding remarks, Maccarrone highlighted the similarity in dynamics when it comes to wages policy in both countries but with different trajectories of implementation, which underline the variegated Europeanisation of industrial relations.

— Discussion on Session 5 —

General notes from the discussion

- In the discussion it was highlighted that Serbia lost 800.000 people in the last years due to emigration.

- Workers leave seeking better payment, being replaced by migrants coming specially from Asia (the case of transport drivers).

- The discussion further focused on the changes in some macroeconomic policies in the EU, after a decade of austerity and in the aftermath of the pandemic.

- One reason can be that the EU Commission learned from the anti-EU sentiment growing in the past decade and especially from the fact that in all parliaments radical right parties are now present.

- This might help to explain why the EU Commission supports the idea of a minimum wage.

- This opened the discussion for an important lesson to learn for the radical left: how can we organize and push through our goal without waiting for economic disasters?

SESSION 6 | 4 APRIL 11:30-12:45

Odysseas Konstantinakos, Manuela Boatca, Valentina Petrovic

SESSION 6 — INSTITUTIONS, GEOGRAPHIES AND INEQUALITIES

Unequal Citizenships and the Political Economy of Cultural Differences

by Manuela Boatca, Professor of Sociology and Head of the School of Global Studies, University of Freiburg, Germany

Manuela Boatca discussed the sociology of citizenship and what solidarity means at the EU and European levels.

- Sociologists often pretend to be non-political – which is of course a joke. Interestingly, solidarity is not a big issue in sociological research.

- What was the state of transnational solidarity in the pandemic? We clearly saw a crumbling solidarity at the beginning, like in the 2008 crisis as well as in the 2015 migration crisis — See the example of the “Covid-19 EU Solidarity Fund”.

- We must state that solidarity is not working properly in the EU. This might be explained in part by the “birth right lottery”. We have a coloniality of citizenship, also inside the EU. Anibal Quijano rightly speaks of the “coloniality of power”.

- The EU is home to eight out of the ten countries worldwide whose citizens enjoy the most freedom of visa-free travel. Germany, Spain, Finland, and other EU states rank in the top worldwide states for “passport ranking”. Afghanistan is last on the list, preceded by Syria and Iraq – countries which are too often victims of western bombings and invasions.

- These are also the countries where the refugees to the EU are coming from. We have a passport apartheid in this world.

- Also inside the EU space a hierarchy of citizenship is evident: for example, during the pandemic, agriculture workers from EU Central Eastern countries were providing food for EU Northern/Western countries.

- The opposite of exclusion is not inclusion but access: exclusion directly leads to unequal access to basic rights for the great majority of the world population.

“Power and puzzling” in the Southern Periphery: How and When European Institutions Learn from the Failure of Austerity

by Odysseas Konstantinakos, Department of Political Sciences, European University Institute, Fiesole, Italy

Odysseas Konstantinakos addressed the (paradigmatic) changes in European institutions in the course of the past years and successive crises.

- Konstantinakos case study is about the developments in Greece during and following the years of the Troika memorandum and the following austerity, calling for the elites’ adaptation to new economic and political realities.

- To deal with the global financial crisis (GFC), the monetary policy, which has been inscribed in the EU treaties and derives from the Washington-Berlin consensus, was the basis for an expansive austerity approach based on the “one size fits all” model. The socio-economic, but also political, consequences were devastating.

- Lessons were learned from the management of the GFC. Coordinated solutions and more flexible rules were undertaken to face the economic recession provoked by the pandemic. Yet, this change in paradigm was already in the making before the outbreak of the pandemic, with “more flexible interpretations” by the Juncker Commission, while the economic crisis triggered by the pandemic provided the ideal scenario to implement them.

- Konstantinakos further argues that tools such as the “corona bonds” or the Recovery and Resilience Funds can constitute a new era of progressive economic integration, with states gaining more significative roles in the economic governance (fiscal paths being designed at member-state level then reviewed by the Commission).

SESSION 7 | 4 APRIL 14:00–16:00

Marco relli (Fiom cgil Trieste), moreno luxich (trade Union delegate ficantieri, Montfalcone shipyard), Alberto Manente (trade union delegate Ficantieri, Marghera shipyard), Matteo Gaddi

SESSION 7 — SHIPBUILDING INDUSTRY: LABOUR’S RIGHT AND INDUSTRIAL POLICY

The general situation of the Italian shipbuilding industry

by Matteo Gaddi, Fondazione Claudio Sabattini

- Off-shore ships that can be used for renewable energy production on the sea are very important for the local manufacturing industries (for example, we witness a 64% growth demand in Trieste). 30 ships have already been ordered and 150 more orders are coming soon. The good thing is that these ships will initiate follow-up orders also for maintenance.

- Despite these good examples, we need to understand that the USA are doing much better regarding national industrial policies. They force foreign firms to produce in US ports if the ships are meant to be used in the USA. This secures jobs for US American workers. The USA is much more robust and protectionist regarding its own jobs, so should we be.

- The big issue at the regional Marghera site are the infinite lines of subcontractors. At this plant we have 1000 direct employees, but four times more indirect employees via subcontractors. 82% of the working hours are done by subcontractors. The costs of the directly employed blue collar workers are 50.000€, while the shipyard has to pay only 30.000€ for the subcontracted.

The shipyards of Marghera and Monfalcone

by Trade Union delegates from the shipyards of Marghera and Monfalcone

- The shipyard sector is a challenging area for trade unionists and unions.

- In the years 2006 to 2010 the names of the subcontractor firms changed every two years to avoid taxes and controls.

- Migrant Bangladeshis and Roumanians work closely together, although they cannot speak together.

- The trade union has been trying to support their workers against subcontracting in the last years.

- Besides losing wages, subcontracted workers are often left unpaid at the end of the month. The delegates referred the recent case of a Senegalese worker who complained about not being paid at all, while not complaining about his hourly wage of only four euros (!).

- An urgent challenge for the trade unions is to represent Asian workers, for example from Bangladesh or the Philippines.

- The shutdown of a shipyard destroys the knowledge that has been accumulated from generation to generation.

- Shipyards are important for the steel industry. We need a European industrial policy supporting these central value chains.

— Discussion on Session 7 —

General notes from the discussion

- In the discussion the topics of new contract systems came up, also the difference of regulations between Spain and Italy.

- At the workplaces of the shipyards asbestos is still a massive problem.

- Generally, the enterprises do not want to pay for health services. Without public push they avoid all costs.

- Regarding industrial policies in the EU we see very strong differences to countries in East Asia, like South Korea. There is a strong role of state by planning and support.

- Delocalisation to Central and Eastern European countries is a planned process that has less to do with solidarity amongst EU countries, but is based on the opportunity of accession to cheap labour.

SESSION 8 | 4 APRIL 16:30–18:30

Michele Piga, Tatiana Moutinho, Roberto Treu

SESSION 8 — THE INTERNATIONAL PORT OF TRIESTE: PUBLIC GOVERNANCE IN VALUE CHAINS

This last session was organised by CGIL Trieste and CSI Nord EST/MSS Severovzhod (Consiglio Sindacale Interregionale Fiuli Venezia Giulua/Slovenia).

Introductory remarks

by Michele Piga, General Secretary of CGIL Trieste

- Michele Piga started by focusing on the contemporary world-wide clashes and conflicts, the economic conflicts within EU member states and the necessity of positive impacts from the side of the EU.

- Making use of the example of the port of Trieste, which borders Italy, Slovenia and Austria, Piga highlighted the importance of the sea and the development of new roles for ports not only at the regional level, but also at the EU level.

- Piga also spoke of the attack on wages and labour rights by the successive Italian governments and of the EU neoliberal agenda. Emblematic in this regard is the fact that in Italy, nowadays more than 60 different forms of job contracts coexist.

— Final Discussion on Session 8 —

with Michelangelo Agrusti, Zeno D’Agostino, Roberto Treu, Stefano Malorgio

- The discussion took place between Michelangelo Agrusti, President of Confindustria Alto Adriatico, Zeno D’agostino, President of European Ports ESPO/President of Port Network Authority of the Eastern Adriatic Sea and Roberto Treu, President of Irtucs Friuli Venezia Giulia/Slovenia Cgil.

- The concluding remarks were made by Stefano Malorgio, General Secretary of FILT CGIL.

PROJECT ‘100 SHADES OF THE EU’ | RESSOURCES

>> Further Resources on the 100 Shades’ Project

- The study “100 Shades of the EU” (March 2022, EN) & executive summaries in various languages (EN, IT, ES, HU, BG, CZ, RO, PL, LT, DE, PT, GR)

- An introduction to the study “100 Shades of the EU” by its editors Tatiana Moutinho and Dagmar Švendová (February 2022)

- CrossBorder Talks’ special podcast episode (December 2022) on the “Hundred Shades of the EU” study: an interview with two of the authors Veronika Susova-Salminen and Giuseppe Celi, audio and transcript

- Report on the European Forum Workshop (November 2021)

- Original invitation to the April 2023 Trieste Conference, including full conference programme

- Interview with Tatiana Moutinho about the 2022 study and the Trieste conference (June 2023)

- Podcast series synthesizing the “100 Shades of the EU” report (June 2023)