As the world hurtles towards climate catastrophe, the urgency for a global socio-ecological transformation is becoming palpable. In this article, Jeremy Leaman examines the factors impeding its realisation, from the permissive practices of authoritarian neoliberalism to the challenges of financing, and proposes progressive policy alternatives crucial to avoiding climate disaster.

We asked Jeremy Leaman to share with us his thoughts on the wider social and economic context of the current struggles and what our demands for a just climate policy need to be – hence his final chapter on ‘Alternative Policy Options for Avoiding Climate Catastrophe’. He bases his argument on Euromemo 2023.

Roland Kulke

This article is part of transform!’s Economics Working Group Blog Series.

The evidence of a growing climate catastrophe is overwhelming and convincing. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), established in 1992, has been ratified by 198 states; the 28th annual Conference of the Parties in Dubai (COP28) is scheduled to address this acknowledged urgency; it will discuss in particular the recent AR6 Report by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPPC) which published new and alarming data of the ‘tipping points’ of key climate indicators having in part already been triggered, ahead of previous forecasts; the World Meteorological Organisation has recently concluded that there is a 66 percent chance that global temperatures will exceed the 2050 target of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels between 2023 and 2027 already. Furthermore, the necessity for national and international action to both prevent climate catastrophe and mitigate the damage already wrought, is invoked by leaders of the G7 group of advanced states, by the European Union with increasingly rhetorical force. There is a handful of dissenters from this consensus (including former US President Trump), but the ‘green’ narrative remains deeply embedded in both civil society and social elites.

Notwithstanding the overwhelming consensus among climate scientists and the popular acceptance of their findings, there remains a significant and predictable gap between the perceived urgency of ensuring the survival of mankind and its biosphere on the one hand, and the political capacity/ preparedness to act decisively to prevent climate catastrophe on the other. This relates in large measure to sustaining the cost of such action, consistently and equitably. How much will the prevention of climate catastrophe and the management of the transition to sustainability cost, in fiscal, social and political terms? Who will bear the financial burden of such a global, multilateral programme? Who will formulate, monitor, and adjust that programme when circumstances demand it? On these and related questions there is still no agreement within and between nations. There are a mere 27 years remaining to achieve the official target of global temperature rise of 1.5 percent above pre-industrial levels set by the Paris Agreement on Climate Change in 2015, with interim targets of greenhouse gas emissions to peak by 2025 and to decline by 4.3% by 2030. There are, as noted above, fairly terrifying indications that these targets were by no means ambitious enough to halt an accelerating climate crisis, and that the scale, quality, and distribution of climate change finance has not been resolved appropriately.

The obstacles to the timely implementation of emissions-reduction and the limitation of global warming are various. Some are contingent, like the monstrous war in Ukraine and the political aftermath of the Covid-pandemic. Others are structural: the constellation of global international relations and the persistence of hegemonic political rivalries in particular; of core significance and the focus of this brief article is the pathological state of the world’s dominant economic model of authoritarian neo-liberalism and the chronically unequal ownership structures and processes of financialised capitalism.

Permissive, authoritarian neoliberalism

While the fundamental imperative of socio-ecological transformation is the survival of a viable planetary biosphere and stable democratic civilisation, the imperative governing neoliberal financialised capitalism is the extraction of economic value and the accumulation of economic wealth. The structures and processes of this accumulation are embedded in the legal guarantees of property rights provided by state jurisdictions. The neoliberal “revolution” of the late 1970s and early 1980s, associated with the market fundamentalism of the Chicago school of economic thought, reinforced the legal and ideological power of asset ownership through state programmes of deregulation and privatisation and the “liberalisation” of exchange controls and currency and capital markets. The Washington Consensus replaced the Keynesian Consensus of post-war years; state authorities were expected to lessen their role as active market agents, confining themselves to the conduct of monetary affairs and the maintenance of social order. This shift proceeded from the political/theoretical/ideological assumption that the allocation of resources and economic investment were best left to private markets and the private owners of economic assets. Central to this modified capitalist system of economic activity was the vastly increased role of the financial service sector, notably in the key financial hubs of New York, London, Tokyo, Paris, Frankfurt and Luxembourg.

While the profit-motive and the “hunt for yield” had always been core features of capitalism, neoliberal financialised capitalism has been increasingly characterised by the commodification of any legal asset, the trading of which yields a financial return, and, above all, by the radical contraction of time between the purchasing and the sale of an asset. Commodification and short-termism have neutralised the efforts of public authorities to plan and incentivise longer-term investments that enhance human welfare and social stability. The neoliberal state permits the conduct of short-term trading which is driven technically by algorithms that exploit infinitesimally small increases in the market value of currencies, equities, commodity futures etc. in order to generate immediate profits for the owners of those “assets”. Arguably the most crass example of short-termism (and fraudulent commodification) are the block-chain technologies designed to facilitate the unimaginably fast sale/purchase of fictitious “assets” – cryptocurrencies, non-fungible tokens – that have attracted $billions into a sphere of economic activity that is of no benefit to the sum of human welfare. Cryptocoin-“mining” consumes 0.5% of annual global energy consumption, which puts it currently above the total electricity consumption of the Netherlands and 187 other countries![1]

While the commercial future of crypto-trading is uncertain, the permissive toleration of such activities by most advanced states and their failure to either regulate or, better, outlaw what is environmentally damaging and socially useless, underscores the negative role of neoliberal practice in environmental affairs. The rhetoric of the Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the EU-Commission’s “Green Deal Industrial Plan for the Net-Zero-Age” is undoubtedly green but, so far, the practice betokens a lack of urgent reflection on the pre-conditions for socio-ecological transformation. Above all, the reliance on private Climate Finance to date has been called into question by recent research (Bracking 2021; Bracking & Leffel 2021; Baines & Hagar 2022); firstly, within a financial services sector accustomed to the high rates of return available from high-speed trading, shorting, SPAC-Funds, hedge-funds, private equity funds et al., the benefits of green bonds, climate bonds, species bonds, sustainability bonds etc. need to very attractive to sustain long-term commitments by financial investors. Sarah Bracking suggests strongly that the increased scale of the market for green finance – to $500 billion in the last decade – may reflect a public relations strategy (of “green-washing”) to protect the reputations of major corporations: “a financialised spectacle of climate change action, which obscures both the empirical reality of ecosystem and biodiversity and the uncomfortable imperative of how our ways of living need to change” (Bracking 2021a). Baines and Hagar demonstrate that the biggest asset management funds – Blackrock, Vanguard and State Street – trumpet their green credentials in expensive advertising campaigns loudly; however, their voting behaviour in the AGMs of the “carbon majors” (oil, gas and coal corporations) are shown to consistently favour the resolutions tabled by the executive boards of those corporations; the authors conclude that “rather than promoting environmental stewardship, the Big Three are better characterised as stewards of the status quo of shareholder value maximisation” (2021: 14). The evidence for greenwashing is strong and reinforced by the less well-publicised intensive lobbying by the Carbon Majors in Brussels and elsewhere. On the strength of the research literature on green finance, Bracking and Heffel (2021) conclude that the market-driven allocation of green investment is deeply flawed, urging a strong “strong return to public authored finance and governance”.

The more recent emphasis by both the EU’s Green Deal Industrial Plan and the US Inflation Reduction Act on public grants to incentivise private green investors is a part-acknowledgement of the inadequacy of privately mediated green finance; nevertheless, debates by policy-makers, scientists and civil society express fears of inter-regional and/or international location-competition (c.f. Altvater) to attract inward investment and a corresponding danger of corporate tax- and regulatory arbitrage[2]. The charge of protectionism in relation to US policy and the IRA raises the more salient question of the geographic reach of public green finance and the very real danger of less developed countries losing out on the benefits of such investment projects. This could severely weaken the fragile consensus around the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and sense of injustice expressed by states in the South, threatened by the effects of climate change (rising sea-levels, drought, extreme weather events) for which they are not responsible. An UNCTAD report from November 2022 outlined “actions to support least developed countries in the global low-carbon transition”, recording that “the world’s 46 LDCs, home to about 1.1 billion people, have contributed minimally to CO2 emissions. In 2019 they accounted for less than 4% of total world greenhouse gas emissions. Yet over the last 50 years, 69% of worldwide deaths caused by climate-related disasters occurred in LDCs.” This reflected not just the huge disparities in economic development between North and South, but also the effects of the macroeconomic straitjacket imposed on LDCs by the monetarist conditionalities of the IMF’s notorious Structural Adjustment Programmes. (REF) Debt Book The OECD, in a 2017 report, estimated an investment and infrastructure gap of $95 trillion in developing countries over the 15 years between 2016 and 2030 in sectors critical to the decarbonisation ambitions of the Paris Agreement (Mirabile et al. 2017: 2). Furthermore, the OECD calculated that developing economies would require 60-70 percent of all global climate finance to achieve the agreed targets. The COP-15 conference in Copenhagen committed developed countries to provide climate finance of $100 billion p.a. to developing countries up to and beyond 2020; this pledge has yet to be fulfilled, reinforcing doubts that the volume and an anything like an equitable distribution of climate finance can be sustained over the next critical decades.

In summary, the accumulation regime rooted in neoliberal principles of market “freedoms” continues to hinder the realisation of goals of the UN climate change ambitions: the extreme short-termism of financialised capitalism is matched by the limited time horizons of state budgets, the tyranny of arbitrary debt and deficit ceilings and the associated unpredictability of temporary multilateral pledges on the volume and distribution of funding to mitigate the growing dangers of climate change.

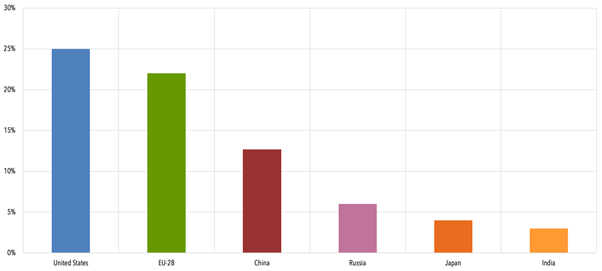

Cumulative Emissions 1751-2017:

Alternative Policy Options for the Avoidance of Climate Catastrophe

The political and academic communities of the progressive Left were always highly critical of the paradigm shift from the Keynesian model of economic management to the neoliberal agenda of deregulation, “small state” and monetarism, even if the deficiencies of Keynesian capitalism had been acknowledged. The ideological capture of both policy-makers and of mainstream economics scholars was astonishing, even if the contradictions of the new market radicalism became rapidly apparent – widening social inequalities, falling wage shares, rising profit shares, declining investment ratios, exchange rate volatilities. Above all, the Financial Crisis of 2008 delivered unequivocal evidence of the failure of deregulated financial markets and of neoliberalism’s “failed ideas” (Lehndorff et al.). While the theocratic dominance and the negative effects of market-radicalism persisted after the Financial Crisis, contributing to the multiple “polycrisis” with which are currently confronted (EuroMemo Group 2023), progressive, eco-socialist voices have become louder in civil society debates and in the active campaigns of opposition to the official policy programmes of the US and the EU, sketched above. Those voices have arguably contributed to the increased urgency and scale of those policy programmes and the dissemination of the published findings of climate scientists, not least because of the physical evidence of global warming in recent extreme weather events and their resultant human costs (mortality rates in and migration rates from crisis regions).

Progressive eco-social voices urgently need to maintain pressure on states and groups of states, firstly to remove critical obstacles to an effective socio-ecological transformation (SET) (as outlined above), secondly to promote a widescale acknowledgement of the colossal scale of the climate challenge and the corresponding scale of financial and human resources required to address that challenge and avoid catastrophe.

The notion that humanity and its constituent societies cannot “afford” the financial cost of existential survival – because of the principles of “fiscal responsibility” – is not only insultingly absurd but, yes, unforgivably “irresponsible”. Planetary sustainability and the survival of human civilisation is infinitely more important than any “just war”. States found the resources, the “treasure”, to finance those just wars in the name of humanity. We can and must do the same for the survival of democratic civilisation and of the wondrous biosphere in which we are temporary tenants.

Space dictates that the alternative options for SET are presented as bullet points to inform current and future debates.

- The principle of multilateral, long-term collaboration is central to the success of a multi-annual commitment to planetary sustainability. The SET is inconceivable without the informed and active support of a majority of the world’s inhabitants.

- A mission involving $ trillions over many decades is thus predicated on the promotion, cultivation and maintenance of high levels of socio-ecological literacy.

- High levels of informed, literate debate can only be achieved by neutralising the social, economic and educational disparities that have been allowed to widen within and between world states.

- The manifest injustice of vast personal accumulations of wealth have to be extinguished from democratic societies and from popular narratives of social value.

- The narrative of tax justice and the value of public goods has, conversely, to be nurtured, with environmental health declared a core public good. The global system of tax avoidance, tax evasion and low tax jurisdictions – which costs an estimated $0.5 trillion annually in lost revenue to states with conventional tax jurisdictions (The Guardian November 2021) – needs to be made as unacceptable to the health of democratic cultures as smallpox was until its eradication by a successful WHO programme in 1980.

- The parasitic economic practices of financialised capitalism, as discussed above, should be likewise regulated out of existence; the restoration of punitive rates of Capital Gains Taxes on short-term financial transactions, abandoned after the neoliberal “revolution” would be one valuable option to effectively eradicate Bitcoin-“mining” and other ecocidal practices.

- A multilateral programme of debt-“forgiveness” in relation to the international indebtedness of LDCs to states and financial institutions in advanced economies would facilitate the establishment of a new international financial infrastructure to manage the distribution of climate finance to poorer states.

- The collaborative restoration of steeper curves of progressivity in income taxation worldwide – through the auspices of the OECD – would go a long way to restoring trust in taxation systems and the narrative of “tax justice” (Leaman 2014; 2019; Leaman & Waris 2013).

- The estimated $125 trillion in required global climate finance to 2050 (UN) or $4.3 trillion yearly will be derived to a large degree by tax reform measures as above, but there will be a substantial need for short-, medium- and long-term bond issues to savers and financial institutions with staggered redemption timetables (maturities) as in war-bond issuance (Pettifor 2019a; 2019b).

Remarks:

[1] The algorithmic guesses are known as “hashes”. One recent estimate suggested a hash-rate of 200 quintillion per second (Howson 2022). The Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index (sic) has been tracking the colossal environmental footprint of Bitcoin mining since January 2017, providing sufficient evidence for responsible political authorities to outlaw the cryptocurrency madness on environmental grounds alone. Viz: https://ccaf.io/cbnsi/cbeci

[2] For regulatory arbitrage and the IRA see: https://twitter.com/MLiebreich/status/1657791523642126336

References:

Baines, Joseph & Sandy Hagar (2022), ‘From Passive Owners to Planet Savers: Asset Managers, Carbon Majors and the Limits of Sustainable Finance’, CITYPERC Working Papers, Nr. 2022-04, https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/249674/1/20220200-baines-hager-from-passive-owners-to-planet-savers.pdf’

Bracking, Sarah (2021) ‘Climate Finance and the Promise of Fake Solutions to Climate Change’, in: S. Böhm & S. Sullivan (eds), Negotiating Climate Change in Crisis, Cambridge (Open Book Publishers), 255-276

Bracking, S & Leffel, B. (2021) ‘Private Climate Finance: Fit for Purpose?’, Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 12/4 https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.709

George, Susan (1988) A Fate worse than Debt, London (Penguin)

Huffschmid, Jörg (2007), ‘Die neoliberale Deformation Europas: Zum 50. Jahrestag der Verträge von Rom’, Blätter für deutsche und internationale Politik, 3, 307-319

Leaman, J. (2014) ‘Reversing the neoliberal deformation of Europe’, in: Menendez, A & J.E. Fossum (eds), The European Union in Crises or the European Union as Crises, Oslo, ARENA Report No 2/14

Leaman, J. (2019) ‘Weakening the Fiscal State in Europe. The European Union’s Failure to halt the erosion of progressivity in direct taxation and its consequences’, in: Menendez, A. & P. Teixera (eds), The European Rescue of the European Union? The Existential Crisis of the European Political Project, Oslo, ARENA Report No. 3/12

Leaman, J. & A. Waris (eds, 2013) Tax Justice and the Political Economy of Global Capitalism, London (Routledge)

Lehndorff, S (ed. 2012) The Triumph of Failed Ideas: European Models of Capitalism in the Crisis, Brussels, European Trade Union Institute

Mirabile, M., V. Marchal & R. Baron (2017) ‘Technical Notes on Estimates of Infrastructure Investment Needs’, Paris (OECD), https://www.oecd.org/env/cc/g20-climate/Technical-note-estimates-of-infrastructure-investment-needs.pdf

Pettifor, Ann (2019a) The Case for a Green New Deal, London (Verso)

Pettifor, Ann (2019b) ‘The beauty of a Green New Deal is that it would pay for itself’, The Guardian, 17. September

This article is part of transform!’s Economics Working Group Blog Series.