Talk by Walter Baier at the Executive Board Meeting of the Party of the European Left (EL) in Berlin, 6 July 2019.

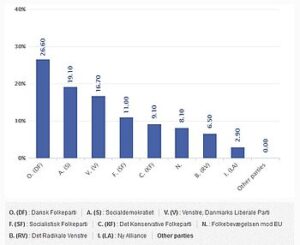

The GUE /NGL and EL suffered a defeat. Except for some notable exceptions – Portugal, Slovenia, and Belgium – and our having maintained significant electoral strength in Greece and Cyprus we lost across the board. Moreover, we must acknowledge that except for the Czech Republic we have no MEPs in the vast space of Central and Eastern Europe.

Given this, it would be a fatal mistake if we allowed ourselves to return to business as usual.

Allow me three remarks:

The first concerns the race between the nationalist right on the one side and the liberal Pro-Europeans and the Greens on the other, which obviously affected us. Certainly, the electoral performance of the nationalist right was below the level generally predicted, while the Greens exceeded expectations. Both nationalists and liberal green Pro-Europeanists have a coherent agenda concerning the future Europe. By contrast, our political proposal was vague and incoherent and so not credible. One month ago, transform! europe hosted a workshop in which we collected reports and the expertise of political scientists in order to draw general conclusions from the elections. Most of the accounts were similar in one respect: European politics apart from rare exceptions played a subordinate role in the electoral campaigns of our parties. Of course, there are reasons for this, for example, the coincidence of European elections with national or municipal elections. However, a general question arises: how can we expect to perform successfully in European elections without dealing seriously with European politics? It is not only a matter of electoral tactics. We all know that the EU’s legislature and administration increasingly limit and constrict national political spaces. Like it or not, EU politics have become a relevant battleground for the left.

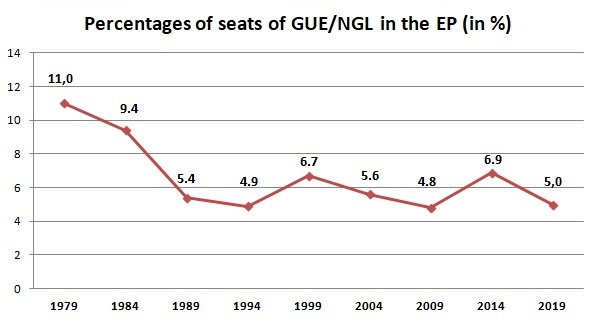

The second observation refers to the historic dimension. Between 1979 and 1994, the first election of the European Parliament to fully reflect the fall of the Wall, the left in Western Europe, then almost exclusively represented by the powerful Communist parties of Italy, France, Portugal, Spain, and Greece, maintained levels between 11 and 9%. In 1994, in the first elections after the end of the Cold War, its share of votes dropped to 4.9%, around which it has fluctuated ever since.

Note: The parliamentary group of the radical left was called the Communists and Allies Group from 1979 to 1989, then Left Unity from 1989 to 1994. Source: website of the European Parliament

This perspective suggests that we must take 5% as the structural electoral strength of the post-socialist radical left, while the 7% it achieved in 2014, represents an exception explained by the particular political conjuncture, which was the struggle against austerity in the European South, symbolised by Alexis Tsipras, then the EL’s ‘top candidate’ for the European Commission. However, we should remember that even in 2014 our gains were concentrated in the European South, particularly in Greece and Spain while the showing in the big Western European countries remained mediocre.

The third observation concerns the passionate controversies among ourselves. None of the three strategic projects (Diem25, Maintenant le Peuple, and the mainstream of the EL) has offered a winning recipe.

Provisional conclusions

It appears that the left is still wrestling with the political reality emerging from the fall of the Berlin Wall. We must once again try to understand the profound changes in Europe introduced by the Treaty of Maastricht subsequent to Germany’s unification

The Treaty of Lisbon, which most of us opposed, not only enshrined neoliberalism as the EU’s basic norm but also boosted also the integration process, both in terms of expansion to the East and deepening it institutionally. Thus, European integration, the crisis of 2007/2008 and the corresponding tightening of the EU’s economic governance have fundamentally changed the rules of the game, revealing the want of a strategic answer on the part of the radical left. This is a serious matter because it does not only concern the EL, and this lack will be even more devastating when the plans for reforming or ‘re-founding’ (Macron) the EU are discussed among the broader European public. Only serious theoretical work and open political debate rather than magical recipes can help.

To be sure, maintaining the GUE/NGL is an important achievement. But what about the party?

We believe that the left in Europe needs a political party on the European level. However, as with any party, the EL’s future depends on its usefulness. It is not inappropriate to critically assess the extent to which the party lives up to the expectations raised by the three elements of its name: ‘European’,’ Left’, and ‘Party’. This carries with it a heavy responsibility since the EL, though doubtlessly weakened, remains for the time being the only party formation of the radical left on the European level.

Generally, the EL has two options:

a) It can be a loose political forum in which parties meet, exchange opinions, and occasionally agree on joint campaigns, a sort of New European Left Forum (NELF). We can allocate funds and capacities in creating a broader forum, as we are attempting with the Marseille/Bilbao/BXL Forum, a space where parties of different families meet and discuss with civil society actors, trade unions, and movements.

This concept is reasonable and coherent. It requires a lean office structure with the task of coordinating rather than ‘doing politics’. The critical question, however, is whether this concept is adequate for coping with the present challenges the left faces.

b) The second option is that the EL takes steps towards becoming a real political actor with its own political profile. Consequently, it would also have to develop a political and communicative capacity and intervene in political debates on the European level. Obviously, such a party on the European level cannot be modelled on national parties since it must be based on inter-party agreements. It requires a concise political platform delineating the framework in which the party is entitled to ‘do politics’, that is, issue statements, take initiatives, and intervene in European public debates. The programmatic platform must be sufficiently broad to address the concerns and interests of all possible partners within and beyond today’s EL.

It is obvious that ‘Europe’ – which is not identical with the EU – must be at the centre of the programme of a European party.

We can build on broad agreement among political actors, trade unions, and likeminded scholars around the core of a progressive socio-economic, feminist, human-rights-based, peace-orientated, and ecological agenda. True, we have to enhance our credibility in all these respects. However, credibility is not only a matter of sincerity but also of the capacity of proposing a strategy for how a transformative agenda could be implemented in view of the current institutional power relations on the different levels of state governance – the local, the national, and the European.

Brexit shows how destructive nationalism is, but at the same time it demonstrates the unsustainability of the EU in its current form. In his letter to the Guardian (4 March 2019), Emmanuel Macron correctly warns against those who would change nothing, as ‘they deny the fear felt by our people, the doubts that undermine our democracies’.[1]

However, the decision made by the European Council on who is to occupy the EU’s top positions is the most recent and most appalling example of the undermining and betraying of democracy – not only in terms of Ms. Von der Leyen, the Commission’s designated president, who is the stoutest champion of Germany’s Military-Industrial Complex, but also for the way in which these decisions were pushed through. Cynical horse-trading behind closed doors while ignoring the results of the election – could one imagine greater scorn for a democratically elected Parliament than the one currently evidenced by the heads of states. These are not minor questions since they touch upon the very core of the political. The current European treaties have established a system of governance meant to impose neoliberal policies on the Member States and prevent democratic change, instead of providing the political space for it. In addition to the socially devastating effects of neoliberalism, the democratic deficit in the EU’s constitutional treaties is the source of the continuous decline of European integration and the rise of nationalism.

How to cope with it?

First, democratic integration presupposes respect for the national self-determination of every Member State. Hence, internationalism is not the privilege of the particularly dedicated ‘Pro-Europeanists’. On the contrary, it means that the ties of solidarity between left parties exist independently of whether a party prefers its country to be outside or inside the European Union.

Second, of course we are in favour of individual citizen participation, referenda, European citizen initiatives, etc. But, democracy essentially implies collective representation of the common interests of social and political groups. The ignoring of the European Parliament demonstrated by the head of states in the selection of the top executive posts once again shows the need for a fully-fledged European Parliament exercising sovereignty over all matters under the EU’s jurisdiction.

Concerning our ‘left’

1) Obviously, only a part of the GUE/NGL’s MEPs will commit to the EL. This means that in reality it is the party of only a part of Europe’s left. Acknowledging this does not mean being satisfied with it. We need to initiate a sincere dialogue with those inside and outside of the EL. There are criticisms about the party’s strategy and modus operandi that are worth taking seriously.

2) However, equally important would be identifying projects for concrete cooperation, for example, initiating a discussion with left actors in CEE and in Scandinavia on common concerns regarding military and security policies as well as looking into how relevant the concepts of neutrality, non- alignment and nuclear free zones, regional or pan-European, could be for a comprehensive security strategy of the EL. We should generally encourage regional cooperation of EL parties (for example, between those of the European South, CEE, and non-aligned countries) and create networks with actors outside the EL.

3) It would be a good exercise in practical solidarity to propose to the EL congress the launching of a common political campaign of diverse left forces. Why not support the excellent idea proposed by Maintenant le Peuple of launching a campaign against tax evasion?

4) A party needs an efficient mechanism of internal and most importantly external communication. In this respect, one could also consider the establishment of an electronic media outlet (maybe in cooperation with transform!)

5) Definitely an issue for the discussion leading up to the congress should be whether a more participatory party structure could lend a new dynamic to the party. Transform! is available to collect experiences with already operating models (for example, online instruments) and submit this for discussion.

It is obvious that the problems are complex and to great extent are a reflection of the bigger picture, the crisis of European integration.

Therefore they cannot and will not be solved within the next five months prior to the congress. But the congress could be the starting point of a thoroughgoing debate. It could, for example, decide on a roadmap, tied to a next congress in which the debate could be connected to substantial decisions concerning the future of the EL.

———-

[1] Emmanuel Macron, Dear Europe, Brexit is a lesson for all of us: it’s time for renewal, theguardian.com, 4 March 2019.

Photo: The participants of the Executive board meeting in Berlin (6 July) joined the demonstrations in solidarity with sea rescue missions (Source: facebook page of the Party of the European Left)