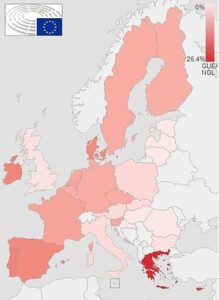

The EP elections were a victory for a neo-liberal agenda and to a much lesser degree for a green one, although here – as in some other EU member countries – the vote for “green” parties served to reduce the vote for the radical left.

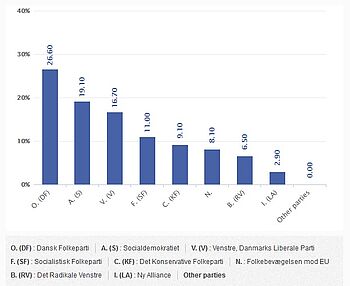

EP elections in Denmark showed a dramatic downturn of the extreme right-wing Danish People’s Party (Dansk Folkeparti – DF), an increase for the Socialist People’s Party (Socialistisk Folkeparti – SF)/member of Green group in the EP, and a significant increase in voter turnout in EP elections – 66 % compared to 56.3 % in the 2014 elections.

But the elections were first of all an upturn for pro-EU neo-liberalism, which does not exactly correspond well with a green agenda, the main topic of the elections. The big winner was the Liberal Party “Venstre”, in government until 5 June, the date of parliamentary elections.

The radical left party Enhedslisten/Red-Green Alliance (RGA), which stood in EP elections for the first time, gained a seat in the EP, but the voter percentage achieved was considerably lower than opinion polls measuring parliamentary scores. The RGA would not have gained its seat without the electoral alliance with the People’s Movement against the EU (member of GUE/NGL), who lost their seat.

There is no barring clause in Danish EP elections (2 % of the votes in parliamentary elections), but the simple fact that there are only 14 seats (13 before Brexit) in the EP for 10 parties/organizations means that the real “barring clause” is quite high, the parties have to reach 5 – 7% of the votes, also depending on electoral alliances. Of course this also means that the impact in the European Parliament is very limited of such a small number of mandates, spread between a number of party families.´

Results

| Party | EP group |

Mandates 2019 | Last EP Election | Votes 2019 (%) | Last EP Election |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Democrats | S&D | 3 | -0 | 21,5 | +2,4 |

| Socialist People’s Party | Greens | 2 | +1 | 13,2 | +2,2 |

| Social Liberals (“Radikale Venstre”) | ALDE | 2 | +1 | 10,1 | +3,6 |

| Red-Green Alliance/ Enhedslisten | GUE/NGL | 1 | (-) | 5,5 | (-) |

| Liberals (“Venstre”) | ALDE | 3 [4*] | +1 [+2] | 23,5 | +6,8 |

| Conservative People’s Party | EPP | 1 | -0 | 6,2 | -2,9 |

| Danish People’s Party (DF) | ECR | 1 | -3 | 10,7 | -15,8 |

| Liberal Alliance | NI | 0 | -0 | 2,2 | -0,7 |

| The Alternative | NI | 0 | -0 | 3,4 | (-) |

| People’s Movement Against EU | GUE/NGL | 0 | -1 | 3,7 | -4,4 |

*13 mandates today; 14 after Brexit; the 14th will go to Venstre-party.

Climate and pro-EU agenda – the political background

The Danish EP elections were strongly affected by the fact that they coincided with parliamentary elections on 5 June. The expectations of the parties’ performances in these elections reflected on the EP elections and vice versa.

The main topic in both the EP electoral campaign and the parliamentary election campaign in Denmark was the climate crisis. There were no limits to how much the parties promised to do in the EP to press for more ambitious climate policies. Many parties presented the climate crisis as one that could only be resolved by “working together in the EU”.

The media were all very pro-EU orientated, which is not new. But combined with the campaigns of some parties, especially the SF, that are both very pro-EU and present themselves as the guarantors of the green agenda in the EU, there is no doubt that these elections also promoted a pro-EU agenda to an extent which we have not seen before.

With the experience of a very chaotic Brexit, it has been relatively easy this time to promote a pro-EU agenda. Easier than if this had been a referendum where you have to decide on a specific issue. But it is still difficult to say if this pro-EU tendency is going to stay.

The necessity to “do something about the climate crisis” was underlined in a big climate demonstration – around 40,000 people – with the Swedish Greta Thunberg as the main speaker on 25 May, the day before the EP elections. This also had a strong impact. The parties and the campaigners were hard pressed by the climate justice movement, which has held huge demonstrations since March, to make them act on the climate crisis. To many parties this huge focus on the climate came as a surprise. Especially the right wing, including DF, was unprepared and had to make a fast turnaround from previous positions and policies.

The climate issue undoubtedly contributed to the exceptional rise in voter turnout compared to the EP elections in 2014. Polls conducted since January show the rapid rise of the climate issue as an election topic. In mid-January 2019 24 % of the voters considered the climate issue as one of the three most important topics in the coming elections. Around the time of the EP elections on 26 May nearly 60 % of the voters picked the climate issue as the most important one, far ahead of number two issue with over twice the percentage.

It should be noted that welfare – which used to be high on the agenda in EP (and other) elections – was less important in the EP elections, also compared to the ensuing parliamentary elections, when it was again a high priority and served to heighten the tension between the so-called “blue” and ”red” bloc of parties (i.e. the right and the left side) in the Danish Parliament, in particular between the two big mainstream parties: The Liberals (“Venstre”), who were in a right-wing coalition government until 5 June, and the contending Social Democrats (SD).

Welfare (and inequality) used to be closely connected to EU criticism in EP elections and referenda. Other important issues in the EP election campaign were social dumping, tax evasion and tax heavens, refugee policies, more control of the financial sector, democracy etc.

General remarks

The right wing

The downturn of the extreme right-wing Danish People’s Party is not a sudden feature of the EP elections. It has shown for some time in the opinion polls and also strongly affected the parliamentary elections. In the EP elections this meant in particular a transfer of votes from the DF to especially the Liberals in “Venstre”, the winners of the EP elections, and to the Social Democrats. Both of these parties have also to a large extent pursued a tough immigration/refugee agenda, copied from DF; i.e. positions of the extreme right can be found in traditional parties.

The success of the mainstream parties especially the Liberals (“Venstre”) and to some extent the Social Democrats (SD), who kept their 3 seats, in the EP elections, reflected more or less the results of the parliamentary elections. It seemed to be a result of a development in the Danish Parliament – as well as in the media – where most of the political parties have gradually adopted restrictive immigration/refugee policies or directed attacks especially on people of Muslim background.

At the same time two new even more extreme right-wing political parties presented themselves in the parliamentary elections but not in the EP elections: The “New Bourgeois” party (“Nye Borgerlige”) and “Tight Course” (“Stram Kurs”). Although they attracted only around 2 – 3 % of the voters each in the polls, DF was in for very tough competition. These two parties are even more extreme and right-wing in their proposals for restrictions on immigrants and refugees especially Muslims, than the DF. One combines this with extreme neo-liberal policies, the other promotes what sounds like neo-Nazism. Whereas “Tight Course” just missed entering parliament in the parliamentary elections, The New Bourgeois party gained 4 seats.

The Liberal Alliance Party, a small party participating in the right-wing coalition government until 5 June, didn’t succeed in the EP elections, probably as they are seen as a more insignificant version of the Liberals.

The Social Democrats and centre parties

It is noteworthy that the Danish Social Democrats are doing quite well compared to many Social Democrats elsewhere in Europe, although they have been weakened to some extent compared to their earlier massive impact on Danish politics. In the EP elections they kept their seats and in the parliamentary elections they achieved a percentage of votes just under the one in the parliamentary elections in 2015 but gained one seat.

One reason for their success is of course that they have undermined the extreme right DF by taking over the main message on restrictive immigration/refugee policies. Another is that they have learned from their previous mistakes as the governing party in a coalition with SF and the Social Liberals from 2011 – 2015, and therefore seem to be moving left on welfare.

The Social Liberals achieved a decisive influence on the economic policies of this former coalition government, which pursued clear, disastrous, and unpopular neo-liberal policies with Margrethe Vestager, now competition commissioner of the EU Commission, as the chairperson of the Social Liberals. Most of these policies were adopted with the help of the bourgeois right wing, the Liberals, of the Danish Parliament. This nearly resulted in the demise of SF, who have now regained some of their previous strength.

Due to the electoral alliance with The Alternative, a small centre-left party allied to Yanis Varoufakis’ list ”European Spring” , the Social Liberals gained one more seat in the EP.

This means by no means that the Social Democrats are becoming less neo-liberal. But they are keen to show a more left-wing and welfare-orientated position. In fact the previously governing Liberals (“Venstre”) have also tried to show off a desire to pursue more welfare orientated policies, making them look not very far politically from the Social Democrats, but conflicting with the policies that have actually been pursued by the right-wing coalition government.

But it is also obvious that the Social Democrats are under more pressure this time from the broad and radical left in the parliament, who have become stronger. The SD will not be able to form a new government without the support of or participation of other parties in the government. This means that they may also very well once again come under heavy pressure from the Social Liberals. The SD leader Mette Frederiksen announced a year ago that the SD is aiming at setting up a one-party SD government.

The broad left outside the SD

The Socialist People’s Party had very good EP elections, doubling their seat, promoting themselves as the “true Greens” as members of the Green Group in the EP. But they are also very pro-EU and pro-EU military, including EU army, and NATO. They were in an electoral alliance with the Social Democrats in the EP elections and hope to – again – be able to enter a new government with the SD after the recent parliamentary elections.

The Alternative, a relatively new centre-left party, which is allied to the “European Spring” of Yanis Varoufakis, did not gain any seats. They present themselves as pursuing alternative policies and as the forerunners in the climate struggle and are very pro-EU. In the parliamentary elections as well, they suffered a defeat compared to their first elections in 2015. In an electoral alliance with the Social Liberals they contributed to the significant success of this liberal party in the EP elections. Their voters seem now to vote SF.

Enhedslisten/Red-Green Alliance (RGA), which stood for the first time in the EP elections, gained one seat with 5.5 % of the votes – a somewhat disappointing result, and unfortunately at the expense of the People’s Movement, who lost their one seat. These two were in an electoral alliance. This result of the People’s Movement, a member of the GUE/NGL group in the EP, is also very problematic for the RGA as it will necessarily have repercussions in the debate inside the RGA and may lead to increasing internal controversy. The RGA vote in the EP elections was considerably below the percentage in the opinion polls for the parliamentary elections (around 8 – 9 % at the time) and did in fact impact negatively on the result on the parlamentary elections (June 5th).

There are a number of explanations why the People’s Movement did not do so well: One is the fact that they are not participating in the parliamentary elections, which removed the focus from them as they did not participate in part of the campaign. This also had the negative effect that they were side-lined in the competition between traditional parties on the green agenda. Another important reason is that they are seen as connected to the chaos and failure of Brexit. The political atmosphere among the voters – even before the EP election campaign – has tilted towards a more pro-EU stance than previously because of Brexit. The People’s Movement is advocating a Daxit – a Danish exit from the EU.

Conclusion

With the climate issue high on the agenda of nearly the whole electorate, but with very limited concrete knowledge yet about how to strengthen climate policies, many Danish voters believed that by “doing this together in the EU” would be the way to move forward. There was hardly any debate on concrete climate policies. Many voters did not realize the difficulty of a neo-liberal economy with a free market agenda to be able to reduce emissions and combat climate warming.

Some of the Danish media did focus on the climate policies of the RGA and the Alternative as the most ambitious among those of the Danish political parties, but it was not a general perception, and the voters largely voted differently.

To sum up some conclusions of how to deal with this election result by the radical left, it is obvious that green policies should be an integral part of radical left policies. Many radical left parties did indeed focus on the green agenda in these elections, but too late to play a role in the EP elections. The problem with the Green parties is that they are less concerned with social and economic issues in relation to fighting climate warming. What is needed is a combined social and green agenda with a just green transition, but it should have been developed and strengthened years before these EP elections in order for the radical left to have a strong profile and be convincing on this issue.

The radical left did not deliver on the huge task to explain that the climate crisis is due to centuries of Capitalist growth of the Western world, and that neo-liberalism will prevent rather than enhance the ambitious green policies that our societies need. To explain this in an election campaign is of course difficult. This is also an educational task.

Like the economic policies, the welfare (inequality) and labour market issues should have been more linked to the green agenda – which again is an important task of the radical left.