Over the past four decades, the social and economic structures have undergone massive transformations. Alongside these, the realities of political life have inescapably changed as well: some once mass parties are now struggling to survive or are gaining no more than a few percent of the vote. In a range of countries, protest movements emerge – and disappear – calling for the entire system to be changed. Who votes for the radical left parties in this new configuration?

Is there any social group that is particularly connected to the left, and which can be expected to elect radical left-wing candidates on a regular basis? Can certain patterns common to many European countries be identified in this regard? An attempt to find and name them was made by researchers Luis Ramiro and Raul Gomez, in a debate with Gala Kabbaj and Yann Le Lann of Espaces Marx.

Lost connection with the working class? It’s not so easy.

The contemporary left is often accused of having lost touch with the working class, which historically was both the addressee of the political programs of the social democratic and communist parties and – it is not hard to recall many prominent left activists of working-class origin – the co-founder of these parties. The social left continues to demand the redistribution of wealth and the overthrow of the capitalist logic of profit maximisation, and therefore the implementation of changes that are in the interests of the working majority. However, in many countries these demands do not seem to be reaching this majority. Worse still, the tendency to lose the popular vote has persisted, and in some Western European countries even deepened, for four decades. Is this the result of misguided tactics and strategies by radical left parties, of communication errors, of too much focus on ‘identity’ and ‘cultural’ issues, as we often hear in the media?

According to Luis Ramiro, the issue is more complicated and should be looked at with the historical context in mind. Left-wing parties and their voters’ structures have changed over the four mentioned decades. That period has been a time of enormous transformation in economic and social life. The structures of the economies of Western European countries changed radically as industrial production declined in importance and an increasing proportion of workers were employed in the service sector. This sector requires different skills and imposes different working conditions — it is not just about the often-described disappearance of large industrial plants, where thousands of workers worked together and fought together for their rights. Our societies and daily lives have also changed, and personal freedoms and the possibility to shape one’s own life have widened.

For Raul Gomez, the critical moment in the history of left parties – both radical and social democratic – occurred in the 1960s and 1970s: Deindustrialisation triggered a rapid decline of the traditional working class, which, until then, had been concentrated in factories and industrial centres, identifying with their profession and workplace and conscious of their difference from the bourgeois class. The working class there cultivated its specific culture, including the memory of strikes and struggles for dignity. Voting for social democratic or radical left candidates was part of their identity. With the closure of large factories, however, the number of such voters inevitably declined. In this context, the social democrats and the radical left tried to reach out to new voters – not only service workers (who still belong to the working class, but without the industrial ethos, if only because of more frequent job changes), but also certain segments of the middle class. We are talking about that part of the middle class which, in the new social realities, showed sensitivity to the problems of women’s rights (political and social), human rights and democratic individual freedoms in the broadest sense, or to the increasingly pressing issue of environmental and climate protection. Thus, the leftist programme was not only aimed at workers, who would continue to be interested in issues of redistribution and equality, but also at the middle class, which is not indifferent to issues of human rights and individual freedoms.

Diverse electorate(s)

In the past, it was relatively easy to describe voting tendencies on class terms: it was assumed that (most of) the working class would vote for the left, and other classes would (rather) choose other political representation. This is no longer valid, for any party. Today’s radical left has a heterogeneous coalition of supporters: on the one hand, its programme continues to be attractive to a certain segment of the working class, while on the other hand, some members of the middle class vote for it. A coalition can be said to have emerged between a section of workers and service workers and a section of those employed in sectors such as health, education, culture and the arts, certain branches of the state administration (especially those involved in social affairs, welfare state institutions and redistribution). This coalition is further strengthened by people whose position in the labour market is extremely difficult – precarious workers, the unemployed, and the students.

“Left-wing electorate segments diverge in their expectations of the party, their understanding of the concept of the left, and their short- and middle-term interests.”

Winning the votes of an electorate that is highly heterogeneous and internally divided brings a specific challenge. In today’s European democracies, challenge is common to all leading parties. There is virtually no party whose electorate could be labelled as homogenous or one-class. Each of the segments that make up the left-wing electorate has slightly different expectations of the party, a slightly different understanding of the very concept of the left, as well as different short- and middle-term interests. In addition, these divergences concern not only the economic, redistributive programme (including the core question: whether to get rid of capitalism or to reform it – and how), but also cultural issues, gender and identity politics, attitudes to and integration of migrants and refugees. Creating a programme that will equally seem attractive to all citizens defining themselves as left-wing proves difficult.

However, as Luis Ramiro pointed out, this heterogeneity is not specific to the electorate of the left. In contemporary European liberal democracies, the electorate of virtually every major political party appears complex and far from a given. This is less surprising than it might seem at first glance: if we look at the history of the left (but also of the social democrats or even of the conservative parties), we find that their electorate never solely consisted of representatives of a single social class. Even on the far right, whose recent progress in various European countries successively has often been commented as unprecedented (and worrying, to say the least), the electorate is made up of different groups expressing divergent expectations. Far-right parties, too, must reconcile conflicting expectations on capitalism and market issues (should the state drop all regulation or, on the contrary, should it still support the weak having the “right” ethnicity?), as well as on cultural policies and, of course, positions to be taken on the European Union.

It is therefore impossible to see the cause of the left’s electoral failures solely in the loss of its primary electoral base or mistakes made in communicating with the ‘natural’ working-class electorate. It is worth noting here that it is impossible to speak of a complete blurring of the relationship between the left and the working class in the Western European democracies. It is the workers from the working class or the middle class, not the groups of professionals or upper-class citizens, who still seem more likely to vote for the radical left: Forming a significant part of the voters, they are those who actively fear losing their current income, or losing their job and livelihood.

Precariousness and uncertainty about the future – this is a clear tendency – might thus lead people to vote for the radical left but also for a more moderate left as long as the latter advocates redistribution of resources and equality policies. However, the left has to first win their trust. As both Luis Ramiro and Raul Gomez pointed out, precarious voters tend to abstain from voting at all in the first place. Given that precariousness is constantly growing, and that even a part of the middle classes starts suffering from instability in the job market, reaching out to these abstaining citizens — who doubt any politician could effectively represent them — might represent a key challenge for the modern left.

In this context, the electoral challenge set for the left might be viewed as more complex than in other political parties: The working class contributes a portion of the left’s electoral score, as it gathers the people most exposed to precariousness — but thus also potentially to electoral absenteeism. When, moreover, these voters abstain from political participation, the bigger share of the vote goes to right-wing parties, who do not even attempt to represent the oppressed, the precarious, the non-privileged.

Workers turning far right? A myth!

The belief that working-class voters commonly redirect their ballot formerly cast for the left to far-right parties has been spread by some of the mainstream media, yet it turns out this stereotype is false. Such a belief appeared in the media after Marine Le Pen began to score well in the presidential election in the north-east of France, a historically working-class, industrial region, also after the Conservative Party achieved electoral success in the former ”red bastions” of northern England. In fact, in most Western European liberal democracies, the far right is not the politically most favoured option of working-class voters. While, indeed, the share of far-right votes in the working class has grown, one can also point to countries where its electoral performance in this social segment is relatively poor. As Luis Ramiro put it, ”one thing is to argue that the radical right has increased the vote among the working class. And a very different thing is to say that the radical right is the party most preferred by the working class”.

“Workers disillusioned with the left are much more likely to transfer their vote to centre-right parties, not to right-wing radicals.”

As Raul Gomez pointed out, workers disillusioned with the left are much more likely to transfer their vote to centre-right parties, not to right-wing radicals. It should also not be forgotten that a certain group of workers voting for the right (including, but not limited to, the Christian Democracy) has always existed. This is because people with a conservative worldview, who also happen to exist in the working class, find it extremely difficult – if at all possible – to vote for a left-wing politician who publicly questions the existing social order, undermines authorities and attacks “the natural, essential, traditional values”. It can therefore be hypothesised that the workers who vote for the far right are, for the most part, not voters disillusioned by left-wing or social democratic parties, but conservative voters who are no longer satisfied with their previous right-wing or centre-right representatives.

An additional factor is the disillusionment with the behaviour of the left itself and with the policies of social-democrats parties when, in the perception of the working-class electorate, they fail once in power to improve the workers’ situation (or, worse still, are perceived by workers as actually serving other social classes’ interests).

Therefore, were it possible to identify far-right voting characteristics or common traits among the voters of far-right parties, it would be wrong to consider here belonging to the working class or holding a low-paid, unstable job as relevant factors. Characteristics such as gender and educational level appear to be much more meaningful: men and people with a low level of education are indeed much more likely to vote for the far right.

Racialised voters: voting for equality

Conversely, can racialised voters, former migrant voters having acquired citizenship of a Western European country and their descendants, be considered the electoral base of the left? As Luis Ramiro pointed out, a general pattern emerges here: this segment of voters is statistically more likely to choose left-wing (including radical left-wing) candidates as compared to the general population. This does not mean that leftist and anti-capitalist parties get all their votes in this group, despite a clear tendency to choose parties advocating equality for all citizens: For example, racialised voters are more likely to vote for the Socialists in Belgium, for Socialist or left-wing parties in France, for the Socialists or the radical left in Spain (with predominance of the former), for the Social Democrats and the Greens in Germany. The vote of these voters goes to parties that stand firmly against racial and ethnic discrimination, including in its economic dimensions. On the other hand, however, a higher percentage of voter absenteeism can be observed in this group of voters than in other segments of the electorate. Moreover, the tendency to vote rather for the left and the radical left is not systematic: In the UK, some ethnic groups and communities are absolutely not inclined to vote for left-wing parties. And in the United States, however paradoxical it seems, and although the available data in this regard is of low quality, there is higher support for the Republicans than for the Democrats in some migrant communities, and this high support goes even to candidates positioned on the Republican far right.

“The segment of racialised voters is heterogeneous in socio-economic status, occupation, and capital. Those class differences matter more than shared identities or common experiences.”

Racialised voters are hence not a homogeneous group. This segment includes heterogeneous socio-economic statuses, occupations and capital. Those class differences turn out to be stronger than shared ethnic and religious identities or common experiences. It turns out, however, that racialised voters, among them many who are working-class and precarious workers, i.e. those who are conscious of belonging to non-privileged socio-economic groups, are willing to cast their vote for the left. As Raul Gomez noted, it is yet difficult to establish the most important motivation of racialised voters in their vote for left-wing parties: It may be a mix of social and anti-racist values combined. On the one hand, they might cast their votes according to economic motives, as these voters are more often exposed to holding low-paid jobs or struggling to reach job stability, or facing social exclusion – therefore being keenly interested in redistribution and the welfare state. At the same time, however, they perceive the left as advocating a state and society directed to all as well as devoid of prejudices, while also talking about acceptance and tolerance. Supporting such a programme can be a very important motivation for people who have been attacked, stigmatised and marginalised because of their different skin colour, “foreign” background, and religion.

Women votes matter!

As indicated above, voters of the far right are much more likely to be men than women. On average, women tend to support left-wing and far-left parties in elections more consistently than men. In their case, too, there has been a great global shift in overall voting preferences since the 1970s. Indeed, in previous decades, in virtually every country where female citizens gained the right to vote, they were more likely to choose canddates who were right-wing, conservative, ‘traditional’ – and in some countries associated with the Church – rather than left-wing politicians (and this despite the historical participation of proletarian women in revolutionary movements in Europe). This trend began to reverse about fifty years ago. Researchers do not fully agree on the explanatory factors and whether these factors can be relevant on a global scale. One of these possible triggers, as noted by Raul Gomez, might be the mass entrance of women into labour markets and their facing of the obstacles that the capitalist labour market had placed in their way. The existence of a glass ceiling and mistreatment in the workplace, as well as the actual hardship put on working women to simultaneously perform reproductive and caring duties in addition to their job, may have led women to turn towards representatives of left-wing parties advocating gender equality and fighting against all forms of discrimination. However, this assumption requires further research, while women’s political activism in individual European liberal democracies is a separate issue beyond the scope of this article.

“Parties strongly advocating for women’s emancipation and equality score better electorally.”

Can the radical left see in women an essential pillar of its electoral base? Recent studies of the female vote clearly evidence that many values relevant to the left – including the anti-capitalist left – are simultaneously the values that drive female voters to cast their ballot for a particular party. Women are more likely to vote for the parties that not only explicitly advocate gender equality but also talk about broad openness to others, tolerance, acceptance of identity differences, universal inclusivity, readiness to welcome migrants and enforcing human rights. There is also a noticeable correlation between explicit support by left-wing parties for women’s emancipation and equality in social life and how good these same parties perform in the elections: Parties of the radical left that have firmly highlighted this issue (and backed up their words with action, making women their leaders and faces) got good or above-average electoral results in recent years.

Culturally progressive, economically socialist

There is now no doubt that if the radical left is to succeed, it needs to build a genuine coalition of diverse groups of voters around itself. That coalition must be diverse, which may raise seeming contradictions, being therefore likely difficult to maintain. In modern liberal democracies, fighting for the working class is not enough to win (let us remember that there has always been among workers conservative and right-leaning voters), just as it would be a mistake to assume that the votes of progressive women and middle-class citizens who are open to diversity and sensitive to human rights would suffice.

The optimal and viable scenario would seem to be the creation of a programme and coalition advocating a progressive economic agenda on the one hand, and a cosmopolitan and culturally inclusive one on the other. Such a programme could be attractive to precarious workers, youth, women, an important section of the working class, as well as to certain segments of the middle class. The radical left must run for the next election with a clear vision to present as well as a sharply drafted manifesto that is based on the assumptions above – and which of course would have to be modified and adapted within each country with national voters in mind: Different issues would have to be given prominence in each country, while the effective running of each election campaign would require its own tonality.

Volatile voters – easy disappointments

The left will be fighting – both in the forthcoming European Parliament election campaign and in every subsequent one – for the votes of extremely unstable electorates. It is not only about the internal differentiation of virtually every class and social group, with the increasing difficulties to determine electoral trends within each of them, but also about the very far-reaching impermanence of electoral sympathies. As Luis Ramiro pointed out, voters in Europe are very volatile in their choices, with highly fragmented electoral behaviours and extremely tenuous attachments to a single party. If, in the past, we could traditionally see whole regions dominated by one specific political party, and voting behaviours determined by class affiliation, these times are gone. Individualism applies today more than ever to the vote cast in elections.

“If the radical left is to succeed, it needs to build a genuine coalition of diverse groups of voters around itself.”

Hence, appealing to one social class or one characteristic group is not enough and we have to return to the question of seeking voters on a broad scale. At the same time, parties must be aware that, in modern democracies, it has turned easier than ever for a voter to become disillusioned with the chosen party if that party has not lived up to their hopes and expectations. The problem of such disillusionment is particularly faced by radical parties achieving good electoral results and becoming part of a coalition government. Holding public office is always a huge test for a formation – regardless of its ideological profile – and poses challenges which opposition critics of the government and the extra-parliamentary opposition are stranger to. This is even more so because exercising power and solving problems at government level is particularly complex and fraught with previously unknown risks in the current realities of global capitalism. Clearly, however, it is easier to disappoint voters when the electoral platform promises systemic change, radically egalitarian policies, and a comprehensive addressing of social issues, which is, after all, one of the hallmarks of the programmes of the parties of the radical left. On the other hand, mainstream social-democratic and even centre-right parties have also suffered huge declines in support in recent decades after coming to power and failing, although the promises their politicians made to voters were, by their very nature, much more moderate and amounted at best to corrections of the existing socio-political system. It is not true that, in recent years, only parties of the radical left have brought disappointment to their voters and have therefore faced an exodus of voters. Let’s recall that the current period –not very good years, in fact, for the radical and anti-capitalist left in Europe – were preceded by years full of hope, progress and good results.

Addressing far-right voters? Not the right path

It would be a mistake for the left in the coming election campaigns to try to woo radical-right voters, even those with working-class backgrounds. As shown above, many of these new voters of the far right have never even considered voting for parties that fight for economic equality, diversity, human rights, or environmental issues. It would be delusional to assume that they could be swiftly talked into dropping xenophobic, nationalist, meritocratic, and drastic free-market views during an election campaign. A more promising strategy that could yield a much better outcome would be to fight for the votes of voters from the groups that have been identified above as partly favourable to the left, to consolidate and unite them around the vision described above, in which individual freedoms and tolerance in no way preclude a progressive, egalitarian economic programme (and vice versa). This can be achieved, and some political parties across Europe have already applied this concept with relative success.

At the same time, the left must be aware that other political parties will also be fighting for the same social groups — part of the middle class, the working class, women, racialised voters. In particular, the competitors of the radical left, as experience shows, will be the social democrats and the greens. Successfully convincing voters from the previously identified groups that only the left can truly and competently true, represent them is a much more important challenge than the media-advocated struggle of the left-wing parties to win back voters who have supposedly moved away from the left to the extreme right. Rather, it is among the social democrats, the greens, and the radical left that key choices and the final allocation of winnable seats will be made.

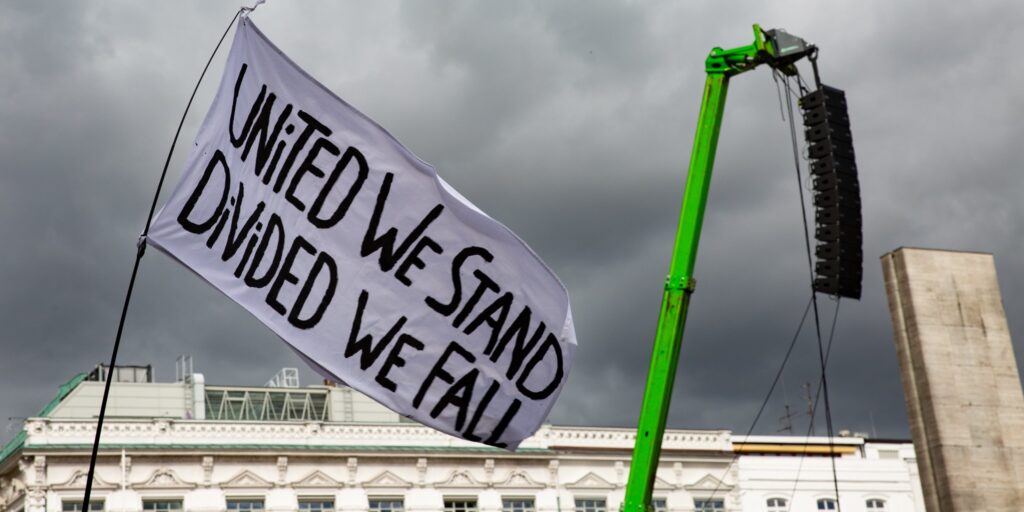

United we win

It goes without saying that, for the left to succeed in mobilising and winning a maximum number of voters, it is also necessary to mobilise within its own ranks. Divisions, internal disputes over secondary issues and an excessive focus on what differentiates various groups and parties have never contributed to a good electoral result, on the left and not only. Only a left that is clear-sighted, well-organised, diverse but not mired in internal destructive disputes will be able to consolidate the heterogeneous coalition of its constituents and, once in power, successfully implement its political demands.

Related resources on transform’s website

- Listen to transform! podcast episodes on this topic, a conversation with Raoul Gomez and Luis Ramiro

- transform! e-publication Identifying and deploying the conglomerate of radical left voters(September 2023)

- transform! e-dossier Who votes for the left and why: in search of our identity, which includes a contribution by Luis Ramiro (April 2023)

The article’s image features a flag with the slogan “United we stand – Divided we fall” in a demonstration on 29 September 2018 in Hamburg (Germany) and was taken by Rasande Tyskar (Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0).