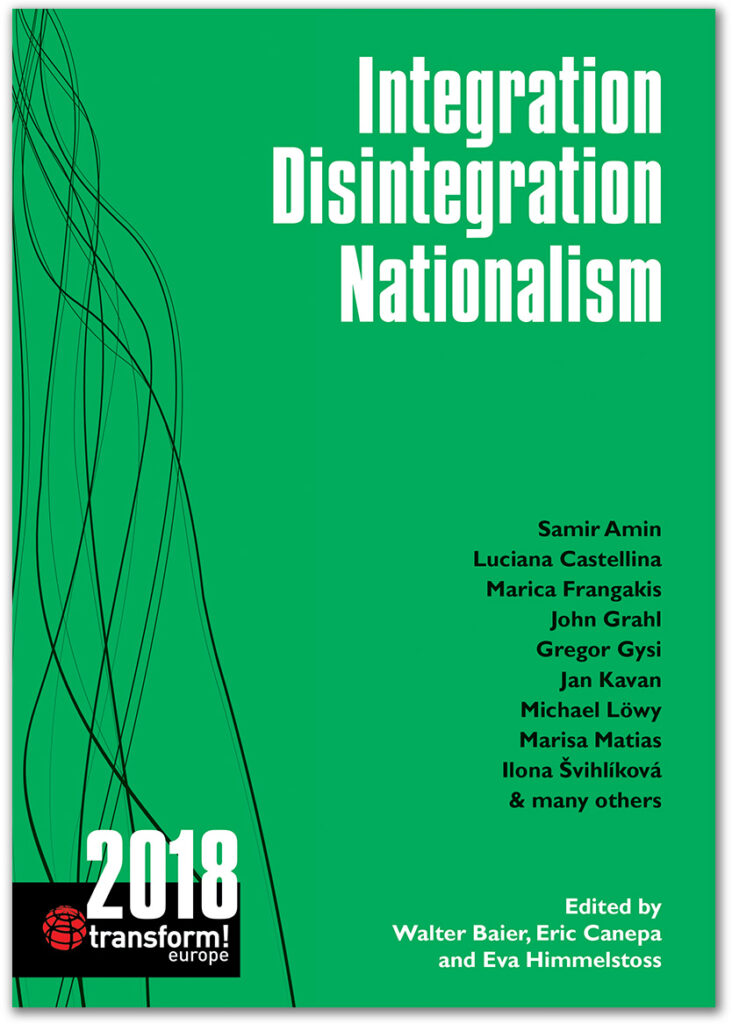

The publication is available here as PDF (or left/below in ‘Documents’).

Read the preface below or jump directly to the table of contents.

NB: The PDF is compressed, leading a few graphs in some articles to be difficult to read in every detail. Please contact transform! for those, and we’ll send you a heavier PDF version, or come back later to this page.

Preface

This volume, the fourth in the series of yearbooks published by transform! europe, is appearing one year before the European Parliament elections. Despite moderate economic growth the process of European integration is in political crisis. Our volume is characterised by a critical evaluation of integration as such.

This kind of stocktaking has to satisfy two requirements: it has to look at European integration and the proposals now being discussed for a reform of the institutions both in the context of national developments and that of Europe’s rapidly changing global environment; and it must also take into account the plurality of the left’s diverse political actors and their points of view. We have tried to accomplish this through an exemplary range of articles.

Transform! 2018 opens with reflections on the state of the world, Europe, and the left. Party of the European Left (EL) president Gregor Gysi discusses the EU’s democratic features and glaring democratic deficits, and the results of Brexit, pointing to the contradictions in the EU’s assertion of anti- authoritarianism as a value. He addresses the need to confront capitalism on an international scale as well as the current situation of the EL. Samir Amin roots the current political crises in Europe and elsewhere in the secular decline of capitalist growth. He discusses China, the new multi-polar world, the room for manoeuvre this opens for the left and left governments, a vision of international left alliances that coordinate people with a limited defensive view and those who want to travel in the direction of system change now, and the relation of the national to the international levels. In a moving testimony, Jan Kavan assesses the dilemma of Europe, the meaning of Brexit, the new anti-politics, and the instrumentalisation, by Poland’s and Hungary’s elites, of fears of an improbable flood of immigrants as an excuse to rein in democracy and promote their economic agenda. Veronika Sušová-Salminen looks at the culture of Western domination in general and the way it plays out in the eastward expansion of the EU.

‘At a certain point in their historical life the social groups detach from their traditional parties’; we see the growing strength of powers constituted ‘relatively independently of the fluctuations of public opinion’; ‘the field is open to violent solutions, to the action of dark forces’. These features of what Antonio Gramsci called an ‘organic crisis’ provide an apt framework for the dilemma of European countries whose polities are removed from decision-making on the most important matters of human society through the extraordinary achievement of market autonomy as a phantom governance of impersonal rules independent of political decision-making even on the part of its advocates – although, as Leonardo Paggi points out, in contrast to the eighteenth-century creed of a ‘self-regulated market’ this market is now seen as a political construction to be protected but not through discretional decisions. The idea is not to rule, just to monitor and punish violations of the ‘natural’ law of the market, resulting in vast depoliticisation. With the single currency, monetary policy can no longer be used to stabilise an economy, creating debtor states which cannot regulate the markets but are regulated by them, like a Foucauldian apparatus. With the collapse of state socialism and the Treaty of Maastricht, the citizenship pact, its culture and vision of society arising from the end of WW II was drastically changed. But as Gysi and Axel Troost point out, contrary to the arguments of right-wing sovereignism, the national states, or rather their elites, are not victims of global processes but enable and transmit them. Meanwhile, the traditional working class parties of the left – having long since co-administered neoliberal policies – have become detached from their base, which is now open to the irrational forces of ethnic-nationalist populism. The traditional mass working class parties, with the possible exception now of Labour in the UK, show no interest in building a left majority with others, and their vote share has sunk too low to enable this in any case.

But with the crisis and the imposed austerity policy, with the Troika’s ultimatum to Greece, with Brexit, and various secession movements, the edifice of integration through neoliberal governance has clearly entered a process of disintegration. Before the Greek crisis, few thought about Europe; now there is widespread resentment of it. It is becoming difficult for the EU elites to hide behind a clockwork of self-perpetuating rules; now harsher, more nakedly political intervention has become unavoidable.

The irony, as Marica Frangakis and John Grahl indicate, is that exit itself, most clearly with Brexit, will only serve to increase Germany’s hegemony over Britain and all others, but the problem for Germany is that its dominance will become more uncomfortably visible, something which the quasi-natural visage of market governance had been partially able to hide.

Ever since the referenda on the Constitutional Treaty, the elites have been able to avoid the risk of democracy by moving decisions to various technical levels. Community decisions were replaced with intergovernmentalism, for instance removing TTIP from the European Parliament’s purview and shifting it to the Trilateral Dialogue. A decision-making hierarchy of France and Germany emerged, with growing German unilateral leadership.

Brexit will increase inequality within Europe: the share of non-Eurozone countries in the EU’s GDP will drop from 30% to 15%, thus strengthening Germany’s political and economic supremacy. And with less Eurozone countries to share the burden the financial markets will worsen the dilemma of the southern Eurozone members. The recklessness of the governing Brexiteers is astounding: Britain needs to at least stay in the Single Market and Customs Union but this will greatly complicate trade by multiplying customs and inspection procedures and, moreover, will keep Britain subject to EU rules but allow it no voice. With May’s fragile majority the political situation is volatile, and the assurances she has already given employers of plentiful immigrant labour could alienate some working-class supporters of the Leave campaign; she has had to promise protection of the labour market. Corbyn’s challenge is to bring together the constituency of the older industrial areas with the more radical youth.

‘Disintegration is not integration in reverse’, as Frangakis puts it; left proponents of exit underestimate both the difficulties of exit and some opportunities for applying pressure that continued membership affords. Forced exit, if foisted on Greece, will be still more difficult, as Frangakis details. Yet even now, before the left grows out of its weakness, it can and should start putting together a critical scenario related to exit. Marisa Matias and José Gusmão are concerned that the reversal of certain austerity measures in some peripheral regions has led many to forget the lesson of Greece and believe there is no need to abolish the current framework. For them, Europe’s left needs to get in synch with Europe’s populations in accepting that the EU will only give us more of the same. Exit is at least possible in their view, and mobilising around it can pull national sentiment in a more progressive direction. They concede it is hard to jump ‘off the train at full speed’ now rather than at the beginning but ‘if we have come to believe that the train is pulling our countries towards the cliff then jumping off right now does not seem such a bad idea.’

The growing popular resentment of the EU institutions has, however, led a section of the elites to support reforms outlined in the European Commission’s 2017 White Paper, which acknowledges some of the evident defects of the existing European construction and the need to remedy them. Transfers, albeit temporary, are being considered, as French president Macron has proposed. Axel Troost and Ilona Švihlíková lay out the much needed reforms, whether seen as goals in themselves or as steps to eventual system change.

The socio-economic and cultural shift represented by Maastricht has its parallel in military and international security policy, as Erhard Crome shows. Just as Maastricht attempted to subordinate political governing to an impersonal market governance and thus diffuse political confrontation, so NATO, as the Warsaw Pact dissolved, could, up to a point, diffuse direct Cold War confrontation, defining new, vastly expanded tasks directed against a vague horizon of ‘threats’ covering almost anything that threatens the socio-economic order. The way in which terrorism and criminality has been projected as omnipresent and boundless has created an obsession with security in large parts of the populations: Dirk Burczyk outlines the problem and suggests ways left parties could tackle it. The US dominates NATO. And the US, through the Washington Consensus, rather than the EU, was the principal actor in integrating the post-communist countries, as Švihlíková points out, for the EU was then still completing its neoliberal turn. But the US offered no Marshall Plan because there was no longer a communist bloc to compete with. The result was the great inequality that is laying the basis for eventual disintegration, whose nationalist right reflection in Poland Rafał Pankowski describes.

As Walter Baier shows in the case of the recent Austrian elections, although right-wing attitudes have been absorbed by a large section of the popular classes, sharp electoral spikes for right-wing candidates generally result at least as much from shifts and arrangements among the elites and their institutions as they do from the sudden emergence of a majority in the population. The figures typically reveal only marginal or negligible voter migration from left to right, as is borne out by Yann Le Lann’s and Antoine de Cabanes’s statistical analysis of the recent French elections. Contrary to the mainstream narrative, the Front National’s vote was not swelled by attracting left working-class voters but expanded through workers and others who had previously voted for the traditional right. Both the radical right and left attract anti-system and populist-friendly voters but not the same segments of this vote. The right-left cleavage is as strong as ever in the minds of voters even if Le Pen and Mélenchon both declared it outdated; those with typical right-wing outlooks vote only right-wing candidates, and those sharing typically left progressive values migrate only among left parties. Le Lann, Cabanes, and Friedrich Burschel thus caution the left against a futile attempt to attract the core of radical right voters, which will alienate most of the left constituency.

The centrist governing elites, either in opposition to right-wing populists or governing with them, are in a waiting game, hoping that the fragile economic upswing in Europe, whose causes and limits Joachim Bischoff analyses, will allow them some more time to continue downsizing social security in doses small enough to be digestible.

We are marking two anniversaries in 2017-2018. An international roundtable with Lutz Brangsch, Patrick Bond, Radhika Desai, Ingo Schmidt, and Claude Serfati debates the contemporary pertinence of key concepts in Marx’s Capital. In particular, the concept of primitive (or original) accumulation as an ongoing process illuminating the global context of capitalism and the relation of class oppression to other kinds of domination and struggles – and the phenomenon of financialisation characterising the contemporary situation, with the great importance of rent-seeking and value capture. And Lajos Csoma commemorates the Hungarian Soviet Republic, rich in lessons, which among other things refute the Hungarian right’s national mythology.

The Estonian Ministry of Justice took advantage of Estonia’s presidency of the European Council last year to organise a European conference on ‘[…] the Crimes Committed by Communist Regimes’. Greece’s Minister of Justice explicitly refused the invitation, explaining his reasons. In the subsequent exchange he critiques the theory, propagated by the new Eastern European elites, of equivalence between Stalinism – or communism tout court – and Nazism, or the theory of a Double Genocide. These letters are surely unique in the annals of diplomatic correspondence. We are publishing them with background provided by Haris Golemis and a survey by Thilo Janssen chronicling the right-wing project to displace post-war Europe’s founding ideas of anti-fascism with an ahistoric and uncontextualised creed of anti-totalitarianism. Leonardo Paggi draws the connection between this politics of memory and the cultural change following Maastricht. Obviously, this campaign is aimed at more than the communist parties per se; its ultimate target is all progressive democratic attempts to intervene in the quasi-natural workings of the ‘economy’, that is, to wrest back and assert the political. It further consolidates neoliberal culture by bolstering the neoliberal project of narrowing historical context and memory.

But there is a bright light in reaction to the dehumanising processes chronicled in this volume and the weakness of the left. Who, a decade ago, would have thought that the Vatican would be at the centre of a dialogue bringing together all who would resist these processes and help people to become politicised subjects of history? It was Pope Francis, in fact, who proposed this project to Walter Baier, the coordinator of transform! europe, and Alexis Tsipras four years ago, resulting in an ongoing project. We are presenting contributions from four participants, Baier, Luciana Castellina, Piero Coda, and Michael Löwy, on the changes within both sides that led to the dialogue and on the political and philosophical context for a consensus on nonviolence.

The transform! europe network was established in 2001 during the World Social Forum in Porto Alegre by a small group of intellectuals from six different European countries, representing left research institutions or journals, who wanted to coordinate their research and educational work. Today transform! consists of 32 member organisations and observers from 21 countries.

The network is coordinated by a board of eight members, and its office is located in Vienna. transform! maintains a multilingual website and publishes a continuously growing number of reports, analyses, and discussion papers on issues related to the process of European integration.

Just like the biannual journal which transform! published from 2007 to 2013, the yearbook is simultaneously published in several languages; it now appears in English, French, German, Greek, and Italian. Expanding our audience and broadening the horizon of the experiences reflected in transform! are not the only reasons why we publish our yearbook in several languages. We do not see translation as a mere linguistic challenge but consider it a way to bridge political cultures that find their expression in different languages and in the varied use of seemingly identical political concepts. This kind of political translation is of particular importance when set against the current historical backdrop of the left in Europe, and it focuses on finding unity in diversity by combining different experiences, traditions, and cultures. It is at the heart of transform! europe’s work.

We would like to thank all those who have collaborated in producing this volume: our authors, the members of our editorial board, our translators, our coordinators for the various language editions, and finally our publishers, especially The Merlin Press for the English edition.

Europe, the World, and the Left

Europe – Its Fault Lines and Future

By Gregor Gysi

A clarification at the outset: ‘Europe’ is used here both as an abbreviation for the European Union and a term for ongoing integration processes, in other words, ‘Europeanisation’. It goes without…

Samir Amin – interviewed by Walter Baier

By Walter Baier , Samir Amin

Walter Baier: The world always has been a dangerous place, but now it seems to have reached its most dangerous moment since the Second World War. Some say it has to do with Trump. Others believe that…

Europe at the Crossroads

By Jan Kavan

Europe is at a crossroads and has been there now for some time. One could even say that a spectre is haunting Europe – a spectre of several fears: fear of terrorism, of Islam, of war, Russia, China,…

From Universalism to Diversity – How to Live in the Post-Western World of Hybrids

It is almost ten years now since the beginning of the Great Recession, and both the European Union as a whole and its individual Member States are still struggling. The Greek debt crisis is not over,…

Confronting ‘Governance’ and Exit – Whither the European Union?

Maastricht as a ‘Civilisation’ – Historical Fragments of an Oligarchical Culture

The crisis of the European Union is developing in a continually more unmistakable direction through the inextricable intertwining of three problems: a) Its interrupted development. The data speak…

150 Years After ‘Capital’ – The EU’s Economic Reforms

Economic reforms for the EU are – once again – in the limelight. Although the prevalent view is that the current situation of the euro area is not sustainable (and certainly cannot be called socially…

Endless Recovery?

The growth rate of global GDP has increased markedly in the second half of 2016. The main contributors to this are the capitalist core countries, and the most important factors for the accelerated…

The European Union – History, Tragedy, and Farce

By Marisa Matias , José Gusmão

There is an apparent moment of peace in the European Union. A moderate economic recovery is being made the basis for a number of quite optimistic declarations and initiatives regarding the future of…

Left Alternatives for Fostering Solidarity in Europe

By Axel Troost

The most recent meeting of the EU heads of state and government perfectly illustrated the strain under which the European project currently finds itself. Today the European Union is facing the most…

The Multiple Aspects of EU Exit and the Future of the Union

A significant change has taken place in the state of affairs of the EU in the aftermath of the global financial crisis in 2007/2008, which morphed into a debt crisis in the Eurozone in 2009/2010. What…

Brexit – Towards the Precipice

By John Grahl

It is increasingly obvious that Brexit is a Luddite project, one that will severely damage the existing productive systems which link Britain to the other members of the EU. Damage will result from…

The EU, NATO, and the OSCE

By Erhard Crome

At a certain level of abstraction one might say that international relations in Europe after the Cold War are shaped by diverse, partly opposed, processes: The integration processes in the framework…

Right and Left Populism – Elections and Security Policy

Between Two Crises? – The 2017 Austrian Elections from a European Perspective

By Walter Baier

A sigh of relief was breathed throughout Europe at Emmanuel Macron’s victory over Marine Le Pen in France’s presidential elections, although in the second round the Front National’s candidate got…

France Insoumise versus the Front National – The Differences Between Far-Right and Left-wing Populism

By Yann Le Lann , Antoine de Cabanes

The electoral cycle of 2017 is a turning point in France’s political landscape; the presidential and legislative elections were a major rupture which upset the political field. Historically, French…

Right-wing Shift – Fast Forward

An ethnic-nationalist citizens’ movement has finally emerged in Germany too, and in record time; and with the entrance into the Bundestag of the Alternative für Deutschland it is becoming normalised. …

The Internationalisation of Nationalism and the Mainstreaming of Hate – The Rise of the Far Right in Poland

Once Europe’s most multi-cultural country, Poland is nowadays the most homogenous nation-state on the continent. Ethnic minorities amount to less than 2 per cent of the population, yet the…

Left Security Policy – Navigating Between the Pathos of Civil Rights and the Lived Realities of Voters

By Dirk Burczyk

In what follows I would like to explore possible answers to the question of public security from a radical-democratic, basic-rights-oriented perspective. This requires first staking out the political…

The Battle Over Public History – Anti-fascism and the New Totalitarianism Discourse

Rejecting Historical Revisionism in Practice – Greece’s Minister of Justice Boycotts the Tallinn Conference on the Victims of Communism

The revision of the history – European and worldwide – of what Hobsbawm called ‘The Short Twentieth Century’ (1914-1991) by means of equating Communism to Nazism has an impact on European integration…

Memory as an Apparatus

The challenge facing European political democracy is reflected in the fragmentation of its historical consciousness. With a new monetary system (1944), the Marshall Plan (1947), and NATO (1950) a…

The Dangerous Conservative Totalitarianism Discourse in the EU

For the centenary of the 1917 Russian Revolution conservative parties of the EU organised a whole series of events dealing with the heritage of communist regimes. The Estonian Presidency of the EU…

Two Anniversaries: 150 Years of Marx’s Capital – 100 Years after the Hungarian Soviet Republic

Marx, Hilferding and Finance Capital – A Roundtable on the Continued Relevance of an Old Book

By Lutz Brangsch , Patrick Bond , Radhika Desai , Ingo Schmidt , Claude Serfati

At the invitation of the transform! Europe Yearbook, scholars from three continents discussed their experiences with Marx. The discussion initiated and coordinated by Lutz Brangsch included Radhika…

The Hungarian Soviet Republic – Revolutionary Movements in Hungary in 1918-1919

By Lajos Csoma

I The wave of world revolution between 1917 and 1923 that swept through the entire globe was a fundamental event of the twentieth century. The Russian Revolution in February 1917 proved to be the…

The Christian-Marxist Dialogue

Dialogue of Critical Minorities

By Walter Baier

During the private audience that Alexis Tsipras, then still leader of Greece’s parliamentary opposition, and I had with the Pope in 2014, which, as L’Osservatore Romano reported, lasted 35 minutes,…

Pope Francis and the Opening of a Christian-Marxist Dialogue

At the second WMPM (World Meeting of Popular Movements), held in Bolivia in 2015, after the first which took place in Rome in 2014, President Evo Morales presented Pope Francis with a cross composed…

The Left and Christian Nonviolent Consensus

By Michael Löwy

A few weeks ago I took part in a Conference in Brescia in honour of the 60th anniversary of Paul VI’s Encyclica Populorum Progressio (March 1967). This document contains interesting reflections on the…

For a Nonviolent Style of Thinking

By Piero Coda

In the brief reflections offered here I am prompted by a provocative idea of the philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas and by an approach enunciated by Pope Francis. 1. Lévinas writes in Otherwise Than Being,…