French academic Estelle Delaine analyses the presence, role and strategy of far-right parties at the European Parliament since 1979 in the perspective of the coming election.

Since entering the European Parliament, how has the far right’s position evolved within the balance of power?

Far-right MEPs have been in the European Parliament since 1979, when universal suffrage was introduced at this level. Depending on the composition of the European Parliament, far-right MEPs may or may not be able to form alliances in parliamentary groups. This is significant, as it’s obviously more advantageous to be part of a parliamentary group (which has a budget, positions to fill, and information etc.), than to sit on the bench with non-aligned MEPs. In this sense, there is no clear-cut pattern, no linear development: the Front National/Rassemblement National (FN/RN), for example, were members of a parliamentary group for twenty-two years, and in Parliament without a group for nineteen years. There have been several far-right parliamentary groups present in previous parliaments, but this is not so in the one currently drawing to a close. The fact is that political parties and even individual MEPs that have been present in Parliament for several governments help maintain these alliances. More generally, the European Parliament is evolving both in terms of its powers and its place in an institutional triangle comprised of the European Parliament, European Commission, and the Council of the European Union. In addition to its oversight and budgetary powers, the European Parliament has gradually acquired legislative powers. Functionally, the European Parliament’s internal political dealings have a stronger resonance as the institution gains greater prominence. What researchers are observing in the ninth term, which ends this year, is the European Parliament’s growing political polarization since 2019. This polarization means that the two historically large groups (PPE and S&D) hold relatively less sway, while mid-sized groups (which was the case for ID) are better represented.

Since 2019, how have the forces of the far right been structured in the European Parliament? Are they able to work together politically?

The far right is clearly an “umbrella concept”, a term that encompasses disparate movements. Observing the configuration of alliances in the European Parliament is useful for understanding the interests of different parties when forming their international alliances. There are several challenges during negotiations: the need to bring together a sufficient number of parties, who agree to present themselves together; the need to link up with numerous partners to show their supporters the real impacts of their support (especially when parties struggle to secure representatives or alliances at the national or local level); and this all while avoiding links to “unpalatable” political leaders or parties that could thwart their attempts to polish the party’s image. In my ethnographic study, I looked at how the ENF group (Europe of Nations and Freedom) in the eighth parliamentary term was structured once negotiations were over. The group’s secretary general at the time used the group’s name to justify the strong autonomous positions of the various national delegations that made up ENF: the nations had a great deal of freedom. This meant that there were considerable disagreements between the member parties, which did not work to build a common political agenda. So not only can the different partner groups maintain their positions independently of their participation in the group — which can be seen, for example, by different voting lists for dossiers in plenary sessions — but they also do not work together on common policies for more commonly-agreed upon subjects like immigration.

What are the political objectives of the far-right forces in the European Parliament?

Close observation of their political practices and activities in situ during the recent term, but also in previous legislatures (recall that their presence is sustained, and that some elected far-right representatives have had thirty-year careers!) highlights the diversity of political strategies pursued by parliamentary groups or, on a more micro level, by far-right MEPs. To suggest that the far right in all its diversity (those who’ve formed a parliamentary group, those that sometimes maintain several groups at once, those that are included in a right-wing majority group like Fidesz before 2021, and those that are non-aligned) have a common agenda would be an exaggeration. This is what is implied by repeated questions in the media about the formation of a “grand far-right coalition” in the European Parliament. On the contrary, by attending to the discourse of stakeholders on the ground, I observed groups who sometimes seemed interested in distinguishing themselves from other far-right formations, as indicated above. My work reveals that groups considered “hard” (e.g, groups formed with the FN/RN) are perfectly capable of participating and fitting into any given parliamentary sub-space. There is no absolute difference between them and political formations considered more “soft”, as was the case with groups like EFDD or IND/DEM in previous legislatures. The attitude and interests of the groups also change. In this sense, elected FR/RN MEPs frequently demonstrated more interest in an oppositional posture than getting involved in the legislative process. Very generally, the objectives of parties that have elected members in the European Parliament is to train their members elected for the first time in the processes of a democratic institution, or to keep them in an office which, after having a parliamentary office for an elected member or an assistant, may be a lobbying office, a consultancy, or in the civil service.

How do nationalist projects take root in transnational institutions?

Nationalist projects predate the advent of the far right in the European Communities. Resistance at a national level to developments that strengthened Europe and political opposition to European federalism, for example, were part and parcel of the history of the European Union long before 1979, when MEPs first began to be elected by popular vote. I think it’s worth keeping this history in mind, and I’d also suggest considering the newness of the European institutions and how they are often discredited. I’m not judging EU institutions here on their vitality or necessity, but we need to see how their slow and difficult path to legitimacy can help us grasp the success of the far right in this political field. Far-right MEPs promote anti-European and nationalist rhetoric by insisting on division and on the fact of their oppositional character. In doing so, they adopt anti-parliamentary postures in a young and weak supranational democracy that provides them with many individual and collective resources. Sociology then allows us to understand how this anchoring takes place in practice: paradoxically, in reality FN/RN MEPs and their team members already have international social capital (whether it be because they have dual nationality, have already lived abroad for professional or personal reasons, or have spouses who are not French nationals, etc.) meaning relocation to Brussels, a city accessible as part of the Schengen Area and partly French-speaking, is conceivable as part of their life paths and careers.

What can the European elections, in particular the level of participation and the social structure of the electorate, tell us about RN voters in France?

European elections have long been considered and analysed as “second-rate elections”, but the 2019 elections saw a resurgence in turnout. This does not imply strong, unwavering support for the RN, since abstaining remains one of the most significant factors in the outcome of the vote. Researchers, following Patrick Lehingue’s lead, point out that the FN/RN electorate is a conglomerate, bringing together loyal voters and those who vote for them more occasionally, those who are convinced and those who want to make a protest or provocative vote, those who vote for the far right or against Europe, and others who don’t read election manifestos or follow debates.

Do you think the vote on the Loi immigration (Immigration Law) makes a coalition between liberals, the conservatives, and the far right possible in France? What about at the European level?

No, but we need to consider what we mean by “coalition”. My answer in the negative means that there is no structured coalition, which would follow a negotiation between the leaders of different political groups who would agree on a political position to defend together and hold meetings to define it. Yet the support, borrowing, and circulation of proposals does not take the form of concrete structures. On the contrary, sociologists who work on far-right ideology demonstrate the capacity of far-right groups to reformulate themselves, to move through political spaces, and to be represented, and sometimes to be convincing, in groups that go beyond far-right milieus, due to political situations or particular contexts, like entering minority government, or elections, etc. In his recently published book, Balsa Lubarda details the morphology of far-right ideas on ecology, their constant reorganisation and their circulation in various political circles (whether far-right or not, more or less proximate to state decision-makers) in Poland and Hungary. As we saw with the Loi immigration (Immigration Law), despite there being no formal alliance with the governing party and no active participation by the RN in the National Assembly, Marine Le Pen still declared that she considered it an “ideological victory” for her party. The European level is a different context but similarly, ID has no formal coalition with the EPP or the ECR and such an alliance is unlikely. However, the very nature of European politics, which is particularly consensual (as MEPs have to agree to write compromised amendments to the texts of Directives and Regulations), leads to convergences, and even situations where the far right compromises with, and votes in line with, the traditional right. This is not the same as a coalition, it’s rather a convergence of votes, or an effect of parliamentary organisation, which I was keen to examine closely during my research there.

What impact could the recent farmer protests across Europe have on the European elections and EU policy?

Collective actions like those of farmers can have the effect of mobilising voters, without the effects being completely predictable: there may be those who feel solidarity with farmers and identify ways of supporting them politically and in this respect, the attempts at political recuperation by RN leaders may not be universally appreciated. Those who, on the contrary, notice the difference in treatment between the actions of this sector and other demonstrators for different causes, leading to a protest vote against the government, which may be directed towards the left, the right, and the far right. But this may not be a problem that affects activists who are already politically engaged. Work by Bertrand Hervieu and Nonna Mayer, Pierre Muller, François Purseigle, and Jacques Rémy on farmers’ protests remains relevant because farmers are well organised to defend their interests in Paris and Brussels and use a repertoire of action that is now routine. We should ask experts on interest groups in Brussels what role agricultural lobbies play, how they are structured and organised, and to what extent they are currently received and listened to by the European Commission, and more nominally — because the predominant institution for considering the demands of interest groups remains the Commission, which initiates Regulations and Directives — the European Parliament’s AGRI committee.

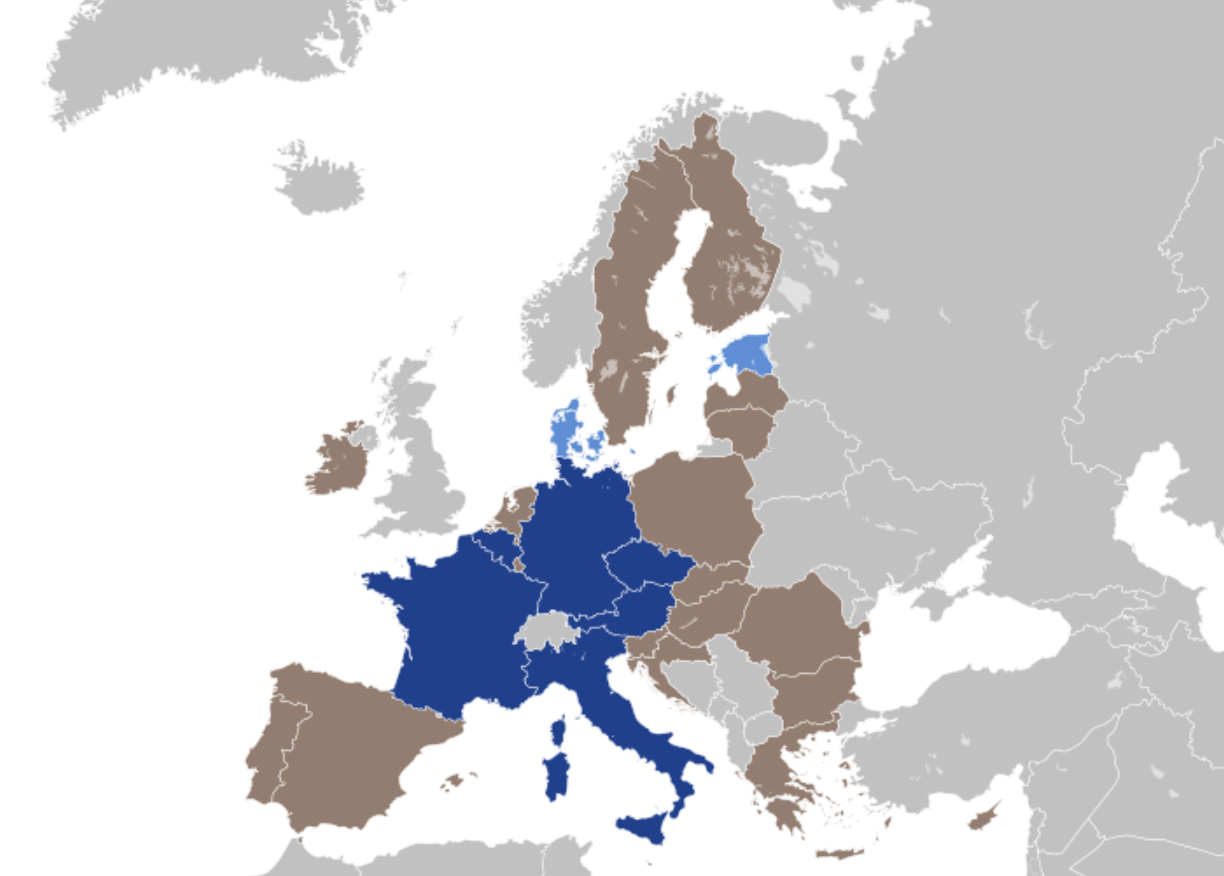

Member states sending multiple ID MEPs

Member states sending a single ID MEP

No ID MEP

Source: Wykx – Own work (CC-BY-SA 4.0) via Wikicommons