Our study on right-wing populism and workers’ unions shows that people’s everyday lives (at work and in their interactions with the welfare state) provide fertile ground for right-wing populism.[1]

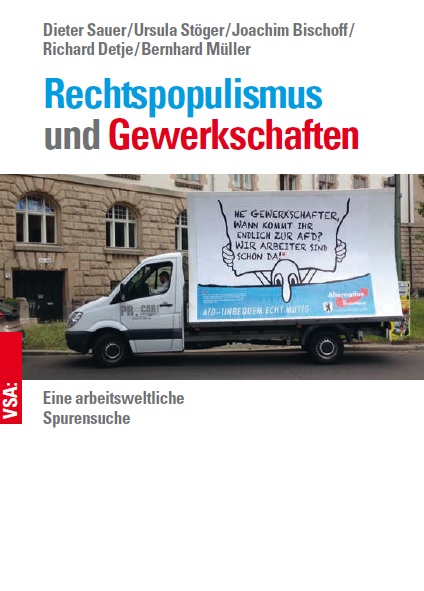

The investigation painted a nuanced picture of how right-wing populism manifests itself in places of work. Those surveyed reported a broad spectrum of tangible evidence of right-wing populism in the workplace, ranging from the cautious voicing of apprehensions and fears regarding refugees to explicitly xenophobic and racist statements at work or on social media. There were also reports of involvement in Germany’s far-right AfD party (Alternative für Deutschland) and even mention of the party’s infiltration through workforce representatives.

There is generally talk of a ‘change in the overall climate’ that took hold during the influx of refugees in 2015. This event acted as a catalyst. The sheer number of those seeking refuge and the obvious lack of government control over how the vast numbers of asylum seekers were managed triggered and stoked fears and resentment. The tremendous feeling of anger that we noted in our earlier studies is continuing to intensify in the face of the further deterioration of working conditions and heightened conflicts surrounding distribution. The refugees became a scapegoat for workers’ own social hardships and anxieties.

Those employees who were already more drawn toward the right are now beginning to express their views more openly and vocally. Statements concerning refugees usually follow a simple line of argument: ‘look what they are taking away from us’. This xenophobic attitude expresses a form of everyday racism where the lines between provocative statements, which are not firmly entrenched in right-wing prejudice, and verbal stigmatisation and marginalisation that subscribes to radical right-wing views become blurred.

Gradual development

No direct correlation exists between conditions in a place of employment and political attitudes: the connection must be made through several gradual steps. And, of course, there is no inevitable link between the situation in a place of work and right-wing views.

Most of the workers we interviewed began by giving a general overview of the state of their place of work and their exact working conditions. Generally speaking, interviewees spoke of experiencing deterioration. Here the point of reference is not a specific situation where workers could make a blanket statement and say that ‘everything used to be better’; rather, their experience is one of continual upheaval. Continuous pressure and permanent insecurity concerning their jobs, income and working conditions were perceived as a ‘crisis’. When we asked about the background elements causing the issue, respondents mentioned the constant restructuring of processes within the company. This included splitting up teams, outsourcing work, competition between sites, cost reduction measures, increased pressure to improve performance, as well as other factors.

These views were already present in our two previous studies on crisis awareness, which were conducted in 2011 and 2013. Here we noted that the impact this ‘constant state of crisis’ was having on workers was perceived as being worse than the actual economic consequences of the 2008/09 financial crisis. And this experience of facing a continual threat posed by permanent restructuring gives rise to a subjective feeling of increased insecurity and dissatisfaction, which, in many cases, leads to anger or resignation.

Further exacerbation

Since we conducted our studies into the crisis, it is our view that the situation in places of work is becoming even more exacerbated. Today’s workers are under almost constant pressure with no respite. Complaints about growing pressure at work are nothing new; streamlining, the boosting of operational efficiency, has become part of everyday working life. However, performance policy has taken on a new level in terms of putting workers under pressure, and this is combined with sometimes excessive forms of flexibilisation. Even after companies have ridden out the worst of the financial crisis, they continue to push for restructuring processes, which involve measures such as closing plants, cutting jobs, optimising performance and pushing strategies that promote precarity. One example is Siemens’ ‘profit center’ concept.

This is compounded by the neoliberal restructuring of social welfare systems, which removes a number of safety nets for workers. A permanent state of crisis thus not only means insecurity, tension and employees pushed to their limits; it also brings with it, at least in parts of the workforce, a downwards spiral of worsening employment conditions.

Those behind Germany’s prosperous economic model paint a different picture, one where conditions for growth, wealth and jobs have never been better and in which fears of social exclusion are on the wane. This discrepancy between the official image and the employment and living conditions experienced by workers has thus grown larger.

Fast-paced restructuring

What we are talking about here is an intensification of the situation facing workers. Alongside market-driven restructuring processes, which have been in place for some time but have increased in intensity and scope, we are now seeing the advent of concepts such as digitalisation, decarbonisation and new supply chains, which act as a catalyst, cranking up the speed of reorganisation.

Our intensification theory therefore not only encompasses a push for improved performance by asking workers to do more, but the broader perspective of a work-orientated society whose regulatory and guidance frameworks seem to be effectively unravelling. Of course, this intensification also entails an advanced-stage precarity of working conditions, but also what is perceived as a loss of recognition and a violation of dignity among the seemingly secure core workforce. A worker is expected to deliver peak performance, but they are also being given the message (albeit indirectly) that their work is no longer valued. Fears of exclusion, as well as of a loss of control and of prospects, are the consequences.

It is not only social pathologies and social instability that lead to the spread of right-wing populist and right-wing extremist views; fertile ground for such opinions already exists in places of work.

Imagining new frameworks of rules and governance

This is where right-wing populism enters the discussion with its promise to deliver security and order (take, for example, the much espoused ‘wall’ narrative). The belief is that through isolation, we will effectively be able to imagine a new framework of rules that offer a new perspective: from the vertical ladder of the contradictory capital–work trope to a horizontal dichotomy between the ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’: ‘us’ vs ‘them’.

Neoliberalism revived the capitalist promise as a form of social utopia: ‘work has to pay again’, ‘every man is the architect of his own fortune’. But in a world where years spent in institutes of education, working hard and adapting to the job market, i.e. making continuous efforts to improve oneself, no longer guarantee a secure income, the idea of an individual shaping their own destiny has lost currency. Neoliberalism’s promise to create a society where we no longer need special ties to get ahead and where the individual is the focal point – the capitalist utopia as imagined by Margaret Thatcher – no longer has a future.

Right-wing populism is a counter-movement and not, as many sometimes conclude after casting a glance at some of the AfD’s policies, neoliberalism in a different guise. This populism does not offer a social utopia for the isolated individual but draws its power from new collective identities.

In the structurally weak regions of eastern Germany, a vast number of problems are cropping up at once. Issues are felt more severely here, be it due to the elevated threat of job loss or the fact that a lack of collective bargaining coverage in many companies has led to even poorer working conditions.

Unique manifestation in eastern Germany

Anxiety about the future and a lack of prospects have manifested themselves in a unique way in eastern Germany. Here the post-reunification period was marked by deindustrialisation, mass unemployment and mass migration: entire regions saw their populations decline. This went hand in hand with the widespread discrediting of people’s achievements as their qualifications and experiences became almost worthless. Further deregulation of the labour market and the vast expansion of precarious employment added further fuel to the fire.

In respondents from the former East German states, we observed a subjectively perceived notion of a loss of self-worth that took on a unique dimension. Moreover, they did not feel supported by politicians and complained that their issues were met with indifference. The result is an increasingly radicalised, critical right-wing view of the establishment.

Resistance against right-wing populism and right-wing extremism should lead to a more in-depth examination of the impossible demands of the market. Here trade unions are stretched on two fronts: trying to boost their organisational strength and their political mandate, while simultaneously pushing for a redesign of labour policy.

Unions need to be given the power to protect wage earners of all stripes – employees, the unemployed, those in precarious jobs and skilled workers, migrants, et cetera – and thus act as an antidote to the right’s promises of security that are accompanied by feelings of anger and resentment. This implies bringing class solidarity into people’s lives and fighting stigmatisation, devaluation, racism and exclusion.

——-

[1] Dieter Sauer, Ursula Stöger, Joachim Bischoff, Richard Detje and Bernhard Müller, Rechtspopulismus und Gewerkschaften. Eine arbeitsweltliche Spurensuche, Hamburg 2018.

——-

Dieter Sauer / Ursula Stöger / Joachim Bischoff / Richard Detje / Bernhard Müller

Rechtspopulismus und Gewerkschaften. Eine arbeitsweltliche Spurensuche.

216 Seiten | 2018 | EUR 14.80

ISBN 978-3-89965-830-9