Brothers in arms: neoliberalism, militarisation, and masculinism are driving a return to traditional gender roles.

“I’ve been a soldier for 30 years”, confided Austrian Chancellor Karl Nehammer on the occasion of last year’s National Day. This may have come as a surprise to those who thought of the chancellor as a neoliberal-conservative career politician. But other European leaders have been making similar pronouncements. For example, French President Emmanuel Macron, an avowed neoliberal, invoked the “steadfastness, trust, strength, and fearlessness” of his “brothers in arms”, standing alongside the US President during his recent visit to Washington.

The connection between neoliberalism and militarism articulated in these statements is by no means solely due to the war in Ukraine. Rather, neoliberalism, current political orientations based on the friend–enemy distinction, and militarisation are deeply intertwined in material, ideological, and emotional terms – and, ostensibly, they drive the resurgence of traditional gender relations as a supposedly unintended consequence.

Material Divisions

As numerous economic indicators show, neoliberal policies of privatisation, deregulation, and liberalisation have led to social polarisation and deep social divisions. Real wages in Austria have fallen considerably, particularly since the financial and economic crisis of 2008, and then largely stagnated before plummeting again due to the currently high levels of inflation. However, the quarter of the population in the lowest income bracket experienced a far sharper fall than the median income. The gap between the quarter with the highest income and the quarter with the lowest is widening, and the divide among the labour force is intensifying. For example, in 2018, executives of listed companies earned 64 times the median income, compared to “only” 24 times in 2003. The income of ATX board members increased by 266% during this period, while the increase in median income was around 34%.

The wage share, which reflects the proportion of wages in national income, also shows how the asymmetry between labour and capital has increased over the past few decades. In the mid-1970s, around 78% of national income went to wages in Austria, while recently it was significantly less than 70%.

Not only is the gap between the growing wealth of the few and the increasing poverty of the many widening, but so too is the insecurity of everyday life.

Furthermore, wealth inequality, which is particularly pronounced when compared to other countries, is also increasing. Half of the Austrian population has no significant assets, while more than 50% of all wealth is in the hands of the top 10%. Accordingly, property income such as interest income, rental income, or corporate dividends are also concentrated in the hands of the few.

Not only is the gap between the growing wealth of the few and the increasing poverty of the many widening, but so too is the insecurity of everyday life, especially as a result of cuts in social services and the precarisation of working conditions. According to a 2022 Eurobarometer survey, 50% of respondents said that their dominant emotional state was insecurity, almost 30% said helplessness and fear, and a quarter said frustration.

Ideological Imperatives

Discourses of freedom and choice, of competition and accomplishment legitimise such growing material social division and anti-democratic social hierarchisation. Defined as relations of competition, they gradually dissolve social bonds; so that the main common ground among individuals is the struggle of all against all. Consequently, individuals are required to exhibit competitiveness, coupled with individual responsibility and entrepreneurial spirit. Their own marketability requires not only the best possible adaptation to the conditions of capital, but also aggressiveness in the form of self-assertion. Criticising social conditions and showing solidarity with others is ruled out almost self-evidently. On the contrary, according to the psychoanalyst Klaus Ottomeyer, when the market form of the subject becomes a question of existence, it systematically promotes “sadistic forms of coping with and calming one’s own fear”. The perception that others are performing better triggers the impulse to eliminate them in order to improve one’s own chances on the market. The suffering and decline of others augurs that one will attain an “optimised” market position and find one’s own strength.

One’s own marketability requires not only the best possible adaptation to the conditions of capital, but also aggressiveness in the form of self-assertion.

It therefore becomes imperative to lack empathy. Not only is the pain of others ignored, but one’s own pain is also suppressed. The German-Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han calls this social constellation, which focuses on the denial of pain, a “palliative society”.

Social marginalisation and exclusion then mutate into personal failure. Those who are unable to adapt to the general marketing of the self and ultimately fail to compete in the battlefield of consumption are not only rightly poor, but also weak and inferior. As a sign of inferiority, poverty is then stigmatised, made a taboo, hidden, lest the only chance left in the competition be lost.

Emotional Distress

By definition, however, competition can only recognise a few “winners”, and since material constraints generate tension and stress, there is an increase in frustration and aggression that becomes attached to objects of projection. Right-wing leaders offer outlets for such pent-up destructive affects: the socially weaker, constantly denigrated “others”, who – in the search for emotional relief – quickly mutate into “enemies”. In a rare case of consensus among Europeans, the right-wing populist discourse that has become mainstream fabricates a homogeneous, culturally superior “us” and an equally undifferentiated, backward, and dangerous notion of the “other”, which grants them a seemingly justified right to rise up and invoke their own superiority – especially in the collective sense of “us” within the national community – which is not only levelled against those seeking protection from war, ecological, and economic destruction, but also against the “enemies of democracy” in the “autocracies of the East”.

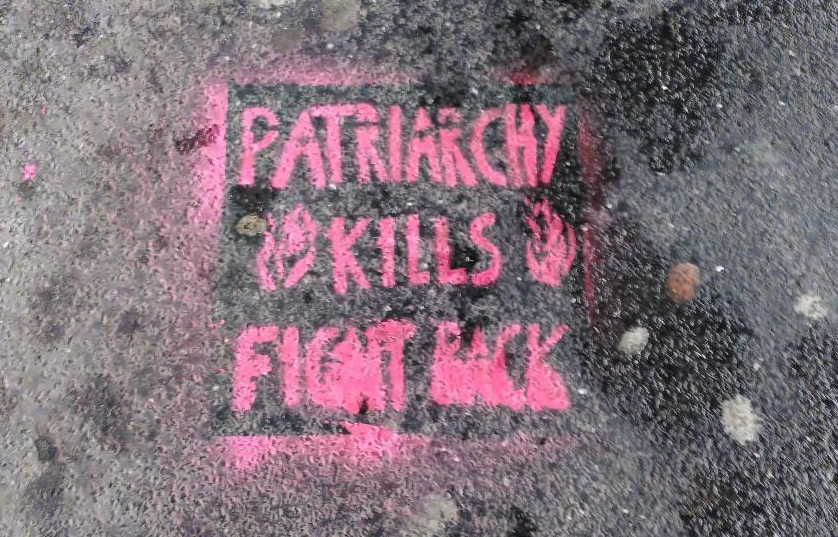

‘Protectors’ of Their “Own” Women

The purported goal is to “protect” one’s “own”, which of course also includes protecting one’s “own” women from “threatening intruders”. While neoliberalism leaves the equality of the supposedly long-emancipated individual woman to her own devices, who could be a “career woman” if she only wanted to, and thus declares feminism to be unnecessary, the recourse to homeland and tradition now implies an aggressive return to traditional gender relations, with the explicit claim of the “natural” superiority of the male “protector”.

Return of the Heroes

Surrounded by enemies, there is always a need for “men of action” who are ready to heroically fight “the others” and mercilessly put them in their place – behind electrified fences and walls topped with barbed wire, at the borders of a territory, so as to mark who the ultimate masters are. However, this also heralds the return to the battlefield of the armed fighter as the epitome of the hero, while women may seek protection in their “cosy home”.

The Weapons Are Back!

Once again, this year has seen an increase in global military spending. The military budgets of the European NATO countries rose from 236 billion dollars in 2015 to 375 billion dollars in 2023. Germany is not the only country striving again for military might with an additional hundred billion euros for the Bundeswehr; Austria, which was formally “permanently neutral” but de facto belongs to NATO, is also rearming. Its military budget rose by 680 million euros to 3.3 billion in 2023. For the coming years, further increases are planned legislatively through a dedicated financing law, ensuring that military spending will amount to at least 1.5% of GDP from 2027 onwards.

Furthermore, support for the armed forces is running high. In a recent survey, 63% of respondents (an increase of 8 percentage points compared to 2021) are in favour of increasing military spending, while 56% (an increase of 13 percentage points compared to 2021) – and thus a majority for the first time – are even in favour of increasing the number of soldiers.

EU Militarisation

At the same time, the militarisation of the European Union is progressing rapidly. Since 2017, Austria has been participating in the “Permanent Structured Cooperation” (PESCO), which was founded by 25 EU states and obliges its members to regularly increase their military budgets, to gradually rearm, to increase spending on military research, and to participate in EU battle groups. Austria also contributes to the rearmament process through various EU financial instruments, the number of which has increased considerably in recent years. While the European Peace Facility, for example, finances EU military missions and equipment for “friendly actors”, a regulation on the promotion of ammunition production, declared as an instrument of industrial policy, came into force in 2023 and will soon be complemented by a “defence investment strategy”.

Governmental Rationality

The EU’s militarisation initiative, highly profitable for the military-industrial complex, relies on a governmental rationality that blends – often with racial overtones – enemy stereotypes, anti-feminism, and masculinism. This fusion serves to obscure social inequality, pervasive precariousness, and economic tensions, while bolstering a capitalism that, in face of the climate crisis, is more dubious than ever. With it, the “protective” patriarchy is gearing up for battle.

First published in Volksstimme, March 2023 edition. Translated by Diego Otero and Marty Hiatt for Gegensatz Translation Collective.

References

Han, Byung-Chul (2020), Palliativgesellschaft: Schmerz heute, Berlin.

Michalitsch, Gabriele (2013), “Regierung der Freiheit: Formierung neoliberaler Subjekte”, in grundrisse. zeitschrift für linke theorie & debatte, 46/2013, 46–51. http://www.grundrisse.net/grundrisse46/regierung_der_freiheit.htm

Ottomeyer, Klaus (2004), Ökonomische Zwänge und menschliche Beziehungen: Soziales Verhalten im Kapitalismus, Münster.

Image: Graffiti in Winterthur, Switzerland; reddit