Analysis from a partner of transform! on the political landscape in Ireland, the Brexit tornado and the European Elections.

Historically, the two dominant parties in national elections in the Republic of Ireland, Fianna Fáil (FF) and Fine Gael (FG), have also dominated in the European Parliament (EP) contests. In 2014, FG and FF both received 22.3% of the first preference vote (in the Republic, the single transferable vote is utilised for EP elections, as well as parliamentary elections to Dáil Eireann, the lower house of the national assembly). FG won 4 seats (from 11 across the state), the same as in 2009. However, FF only managed 1 (down from 3 in 2009). This was due in part to the failure of complex strategies of vote management, and the distribution of lower-order preferences. FG MEPs sit with the European People’s Party. Compounding FF’s woes, its MEP, Brian Crowley was later expelled as he refused to caucus with the Alliance of Liberal Democrats for Europe (ALDE) group and joined the European Conservatives and Reformists group, so FF is currently left without representation in the EP. At the time of the 2014 EP election, the national government in Dublin was a coalition of FG and Labour, and the junior coalition party was severely punished at the poll, losing more than half of its 2009 vote (5.3%, down from 13.9%), and all of its 3 seats. (Quinlan and Okolikj, 2016).

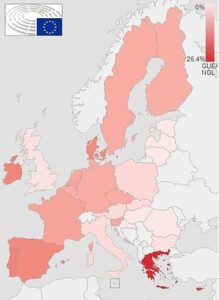

The radical nationalist party, Sinn Féin (SF; usually translated as ‘Ourselves’) produced its best performance in an EP election, winning 19.5% of first preferences and 3 seats (up from zero in 2009). SF MEPs sit with the Confederal Group of the European United Left/Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL), although the party clearly has a distinct ideological heritage, compared to the bulk of the (ex-) Communist parties which founded the group out of the older Communist and Allies group. The other 3 seats in 2014 were won by Independents, and non-party candidates won 25.6% of first preferences (more than any of the established parties), reflecting the fact that all of the established governing parties were held responsible by voters for the severe economic conditions experienced in the Republic since the financial crisis of 2008 onwards. Indeed, the combined vote share for FF, FG and Labour was 49.9%, their lowest ever total. Quinlan and Okolikj have argued that, despite the EU-IMF bailout in 2010, and the expectation that voter attitudes to the EU might take on greater salience in 2014, in fact the results were influenced to a large degree by domestic priorities, and the voters punished the governing parties for the iniquities of the austerity programme which was then in full swing. Turnout in the 2014 EP election was 52.4% (down from 59% in 2009), still above the average across the EU member states.

Contemporary Politics

After parliamentary elections in 2016, Fine Gael now leads a minority government in Dublin, having gained slightly less than a third of the overall seats in the Dáil (50/158). The new Taoiseach (Prime Minister) since June 2017 is Leo Varadkar, but the government has been in a precarious position, given its reliance upon FF votes to pass core legislation. FF won 44 seats, a substantial increase on its electoral nadir of 2011, when it had been reduced to only 20. SF again increased its representation significantly, winning 23 seats in 2016 (up 9 on 2011), although its vote share (13.8%) was a disappointment to the party, and below expectations. Labour was once more the big loser, reduced to a rump of 7 seats (down a huge 26). Independents won 18 seats (up 6), whilst the leftist Anti-Austerity Alliance/People Before Profit grouping managed to win 6 seats (up 2).

The last 18 months in Irish politics have been dominated in large measure by two highly significant developments: first, the fallout and uncertainty created by the decision of the UK referendum in 2016 to leave the EU, and the potential economic and political implications that this may have for the Republic’s economy, and in particular the cross-border dimension of Brexit. There has been a good deal of speculation regarding the likely effects of the UK’s exit upon the 500km border between the Republic and Northern Ireland, with difficult three-way negotiations between the European Commission, the Dublin government and the London government, aimed at avoiding the necessity for a ‘hard’ border (involving customs checks, and potential economic and social disruption). At the time of writing, it remains unclear when (or even whether) Brexit will take place, and also whether it will be possible to retain the ‘invisibility’ which has characterised the border since the ‘peace process’ of the late 1990s became embedded. The implications of a ‘no-deal’ Brexit (withdrawal of the UK from the EU without an overarching agreement) for the Republic’s economy and trade are variously described as serious or catastrophic. The draft withdrawal agreement, which would include provision for all of Ireland to effectively remain within the EU’s customs area (the so-called ‘backstop’) in the event of the EU and UK failing to agree a future trading relationship in the transitional period envisaged, has been defeated regularly in the UK House of Commons.

The shockwaves caused by this vote in the nearest neighbour of the Republic are unlikely to dissipate any time soon, and political life in Dublin has, to a significant extent, been dominated by the necessity of attempting to mitigate the worst effects of this unwelcome decision. For SF, however, Brexit and increasing uncertainty regarding Northern Ireland’s relationship with the rest of the UK, could be viewed as an opportunity: unexpectedly, the party has been able to put the very existence of the border, and the possibility of a referendum to change the constitutional status of Northern Ireland (a poll on ‘unity’), back on the agenda of mainstream political debate. After the Good Friday/Belfast Agreement of 1998 and up until the 2016 Brexit result, despite SF’s best efforts, the border had been fading as a critical issue in the political life of the Republic. It appeared as though, for many on both sides of the border, the issue had been ‘solved’, or at least much of the heat had been taken out of the debate. Now, uncertainty reigns, and SF senses that, as the only significant all-Ireland party, it is well-placed to further its overriding political ambition (indeed, its raison d’être) of ending the partition of Ireland, and creating a unitary state on the island.

Second, in 2018 the Republic held a referendum on repeal of the eighth amendment of the Constitution (passed in 1983), which had outlawed abortion in almost all circumstances. The result was a very clear two-thirds support for repeal, and the FG government brought forward legislation to give effect to this crucial change in the social politics of Ireland in late 2018 (the Regulation of Termination of Pregnancy Act allows for terminations under medical supervision up to 12 weeks gestation). In the wake of the 2015 referendum, which supported marriage equality in the Republic, the 2018 vote has confirmed the impression that the traditional power of conservative Catholicism in the Republic is certainly on the wane, and may soon be consigned to the history books. In a sign of some unrest among conservative opinion, a SF member of the Dáil (TD), Peadar Tóibín was suspended from the party for voting against the legislation, and subsequently resigned, setting up a new party Aontú (Irish for ‘unity’), which will contest the EP election as well as local elections in May.

In November 2018, the voters comfortably re-elected, for a second seven-year term, Michael D. Higgins as President of the Republic. The former Labour Cabinet minister won 56% of the first preferences. The election was a particular disappointment for SF; the party’s candidate, Liadh Ní Riada (an MEP for the South region) won only 6.4%, less than half of the vote for SF’s Presidential candidate in 2011, Martin McGuinness.

Previewing the EP Election

The local elections will be held alongside the EP election in the Republic on 24 May, and this may help to maintain a relatively high turnout. Assuming that the UK does not participate in the EP election, the number of seats contested in the Republic is due to rise from 11 to 13. Under the constituency review process, the country will be divided into three constituencies (Dublin with 4 seats; the Midlands/North/West with 4; the South with 5). Both of the major parties are reluctant to select candidates who are sitting TDs or members of the upper chamber, the Seanad, as this would create potentially difficult by-elections. So, the public profile of FG and FF candidates is not always particularly strong, which can be an advantage for independents and smaller parties. In Dublin, the only incumbent MEP who is standing again is Lynn Boylan (SF), so the campaign here may have a less predictable character. It is noteworthy that Mairead McGuinness (FG) will stand again in the Midlands/North/West; she has been prominent in recent times in the Brexit debates, as a vice-President of the outgoing EP (she was first elected in 2004). On the left, SF will expect to maintain its breakthrough of 2014, whilst the Labour Party remains in the doldrums, and is unlikely to win back representation in the EP. The renamed Solidarity/People Before Profit alliance is unlikely to make significant headway in the EP election, but it may manage to retain its base in local councils (where it has 23 councillors). The alliance is a relatively uneasy umbrella organisation for two parties with their respective roots in two Trotskyist parties, the Socialist Workers’ movement (PBP) and the Socialist Party (Anti-Austerity Alliance, renamed Solidarity in 2017). Historically, these parties have been implacable opponents on the far left of the political spectrum, but they have co-operated in recent years, partly in order to take advantage of speaking rights and funding opportunities in parliament.

In recent opinion polls, the two largest parties have been consolidating their position, with FG currently polling 31% of first preference voting intentions, and FF at 25%. SF has maintained its strong showing at 19%, whilst Labour remains marooned on only 5%. The various Independent candidates are somewhat less popular than in the recent past, with 12%; the Greens are at 3% and Solidarity/PBP have 1%. A new factor in the 2019 contest will be a party campaigning for Ireland to leave the EU; Irexit – Freedom to Prosper has said it intends to stand a number of candidates. The EP campaigns have not really begun in earnest yet, and to some extent the Brexit debacle in the UK continues to overshadow the debates in Irish politics.

References

Stephen Quinlan and Martin Okolikj, ‘This Time it’s Different…but not really! The 2014 European Parliament Elections in Ireland’, Irish Political Studies, 31 (2), 300-14.

Cover photo source: www.indymedia.ie