The clear sanction of the Liberal-Conservative government in the legislative, regional and European elections on May 26 took a radically different form in different parts of the country. While the Flemish (60% of the population) massively voted for the far right, it is the radical and ecological left that triumphs in Brussels and Wallonia.

For political, socio-economic and historical reasons, the electoral sociology of the French-speaking and Dutch-speaking areas has always diverged. This gap looks like an inverted mirror in the aftermath of the election of 26 May 2019. While the total number of votes from the centre-left to the radical left climbs to 61.19% in the French-speaking world for the European elections, it only reaches 27.53% in the north of the country.

Green and red wind in the South

In Wallonia and Brussels, voters first sanction the MR (Liberals), the only French-speaking party in the outgoing government. The undeniable winners are the Belgian workers party (PTB, radical left, 14.59%, +9.1) and Ecolo (greens, 19.91%, +8.22%). The latter, which come second or third according to the elections, have benefited greatly from the environmental social mobilizations underway since the beginning of the year. The progress is even more evident for the PTB, particularly in Brussels where it triples its 2014 score. This performance is symptomatic of the desire to break with the neoliberal consensus embodied by the party, which reaps the benefits of laborious field work.

While maintaining its first place, the Socialist Party (PS, social-democrats), once hegemonic in the south of the country, sees its score exceeded for the first time by the addition of that of the other left-wing parties. The opposition campaign launched in 2014 at the federal level and in 2017 in Wallonia did not allow them to erase from the memories the many cases of corruption and bad governance. Nevertheless, they were able to benefit from a “useful vote” effect, by presenting themselves as the best option to defend social achievements against the right. They were also able to count on the support of the socialist trade union FGTB, and, more broadly, on the associative network inherited from the traditional organisation of Belgian society in “pillars”.

Finally, these elections mark a new failure by racist and xenophobic forces to break through among French-speakers. The people of Brussels, who had not elected any councilors from this side during the municipal elections of October 2018, keep their city fascist-free. The only populist right-wing elected official in the south of the country is disappearing from the local political landscape. More than ever, French-speaking Belgium appears to be a progressive island, in a European sea where the populist right has the wind in its sails.

Black wave in the North

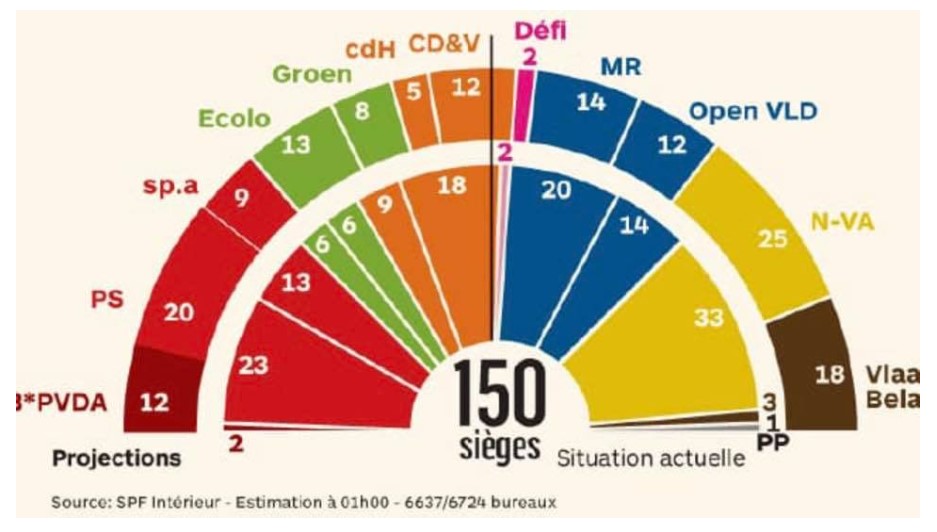

In Flanders, on the other hand, the major fact of these elections is the strong return of the far right of Vlaams Belang (“Flemish interests”), which the conservative nationalists of the N-VA had falsely believed to have taken down by adopting part of their agenda. Falling to 6.76% in 2014, it scored an unexpected 19.8 (+12.32%), which allowed it to move up to the second place. While this party, which intends to limit in time and condition unemployment benefits, does not present any proposals in favour of tax justice, its success is also linked to a more social discourse than in the past. It has enabled it to capture dissatisfaction with the government’s frontal attacks on workers’ rights.

The party has also benefited from the migration issues promoted by the N-VA, whose Minister for Immigration Theo Francken has pushed the issue far in the direction of the extreme right electorate. The defeat of the N-VA ( 26.67, – 4.23), sanctions the failure of this strategy to dry up the extreme right by adopting part of its speech. However, the N-VA does not intend to change it. On the evening of the results, its president Bart De Wever even mentioned his desire to break the “cordon sanitaire”, a tacit agreement between democratic parties to exclude the far right from the political game.

On the left, the Social Democrats continue to erode. The expected green wave did not occur there, as Groen (greens) only made marginal progress. The real revolution is the PTB’s crossing the 5% electoral threshold for the first time at regional and federal levels, which represented a major success for the PTB to exist on both sides of the linguistic border.

Towards confederalism?

The complexity and fragmentation of the result do not provide a clear and unambiguous signal from voters, other than the rejection of policies led by the outgoing majority. While the green and red boost generally pushes the left forward, the pressure exerted on traditional parties by the radicalization of the right augurs a long period of blockage, with a risk to go back to polls.

More fundamentally, the rising of the total of pro-independence forces (N-VA and VB being close to the majority of votes in Flanders) and the widening gap between the two communities brings back to the table the opportunity for a new constitutional reform leading to maximum devolution of powers to the regions. Initially advocated by the pro-independence right, it could win supporters among French-speakers, whose progressive aspirations are thwarted by the federal straitjacket. A scenario particularly feared by the PTB, viscerally attached to the unity of the country, whose slogan “We are one”, sung in both languages, is less and less resonating with the political reality.