Although European elections tend to be second-order in nature, those of 2024 had a first-order impact in several European countries, including Greece. This post-electoral analysis uncovers important shifts in the Greek political system.

Although European elections are traditionally considered as being second-order in nature, it is quite clear that at least those of 2024 have had a clear first-order impact in several European countries, with the snap national elections in France and the subsequent formation of the New Popular Front by the progressive parties being the most prominent example of this.

Greece is no exception here. Of course, it is not uncommon for European elections to have a clear national character, for example with respect to the electoral agenda and the topics that dominate the party campaigns, as well as other factors such as the stakes and the outcomes. European elections are often either the prelude to and catalyst of political change or the confirmation and solidification of political and electoral trends that have already occurred at the national level. In a number of different ways, the most recent European elections in Greece have been both.

Before analysing this claim in more details, let us first examine the main features of the electoral results.

Source: Verian for the European Parliament

https://results.elections.europa.eu/en/national-results/greece/2024-2029/

Where Did All These Voters Go?

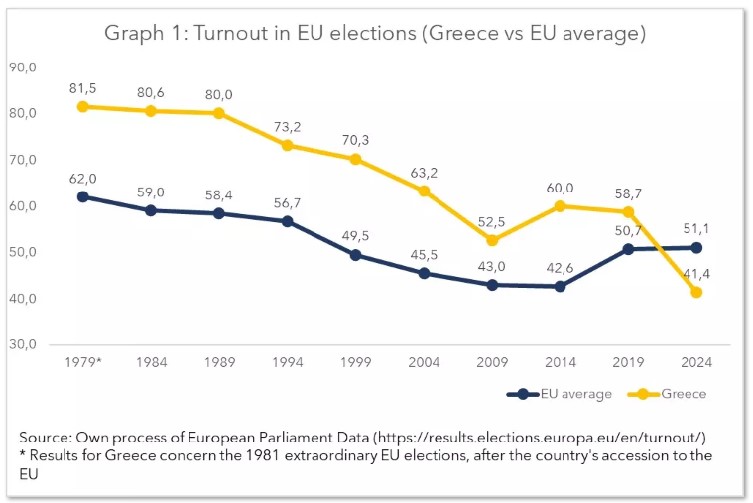

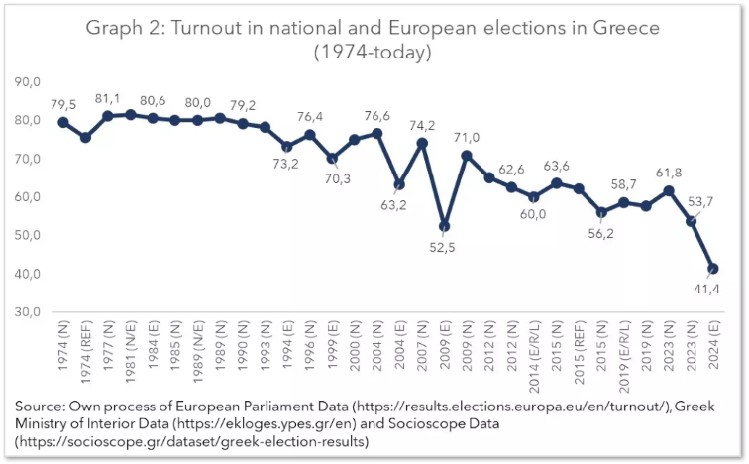

The last EU elections marked the end of the Greek exception when it comes to electoral turnout (Graph 1), with abstention reaching a record high (Graph 2). In comparison to the last national elections of June 2023, when turnout was the second lowest to date, the total number of “lost voters” rose to 1.2 million, or 23 percent of those who participated in the last (June 2023) national elections. Even worse, the number of “lost voters” since the first round of national elections (May 2023), i.e. before abstention started skyrocketing, increased to approximately two million, or 33 percent of the participating electorate.

Although it is not possible to accurately calculate abstention, according to one estimation, almost 717,000 of May 2023 ND voters, 495,000 of May 2023 SYRIZA voters and 203,000 May 2023 PASOK voters chose to abstain in the European elections. In other words, of the two million voters that the political system as a whole lost to abstention since May 2023, 1.4 million (or seven out of ten “lost voters”) had voted for the three major parties.

There are various plausible explanations for the skyrocketing levels of abstention. Many have understandably pointed to objective factors, such as the heat wave that hit Greece during election weekend, voter fatigue following four consecutive elections over the past year,1 and the fact that a lot of Greeks, especially younger ones, are seasonally employed in the tourism sector, meaning they were away from their primary residence.

While it is clear that all of these factors have contributed to the overall abstention rate to some extent, they cannot explain the additional 12.3 percent of the electorate that voted under similar circumstances in June 2023 and chose to abstain on this occasion. In addition, one must not forget that these European elections were the first instance in which the possibility of postal voting was available for everyone in Greece, including those who were both inside and outside the country, which enabled the participation of voters who would otherwise abstain for any objective reason (residence abroad, work, health issues, old age, etc.). In fact, the number of those who made use of this new possibility rose to 178,000, or four percent of overall ballots cast.

It is thus obvious that the reasons behind this very high rate of abstention are instead political in nature, and that we should be looking out for them on two temporal levels: the long-term and the medium-term.

The examination of turnout data over the long term suggests that it is normal for participation to be lower in European elections, thus confirming their “second-order” character (Graph 1). It is also clear, however, that despite fluctuations in participation levels across different kinds of elections, electoral turnout has been steadily dropping throughout the Third Hellenic Republic, declining sharply since the 2008 economic crisis in all types of elections (Graph 2).

Since last year, the ruling party has been stronger electorally than its two main opponents combined, and appears almost invincible. This has left dissatisfied citizens feeling powerless.

The fiftieth anniversary of the restoration of democracy in Greece comes at a time when the grievances of Greek citizens concerning politicians and political parties are accumulating, and their overall disappointment and cynicism is increasing. Although these feelings might express themselves in a more quiet manner than those seen at the outburst of the economic crisis 15 years ago, they now relate to all of the major and potentially governmental parties, thus highlighting the sense of a lack of alternatives.

There is, however, a more specific explanation for the sharp increase in abstention levels in this particular election. First, as explained in a pre-electoral analysis of the Greek political landscape, Greece has been sliding towards a dominant-party system since 2019 — and even more so since 2023. Since last year, the ruling party (ND) has been stronger electorally than its two main opponents (SYRIZA and PASOK) combined, and appears almost invincible. This has left dissatisfied citizens feeling powerless.

In a way, the prevailing theory, according to which a dominant-party system usually sees any political confrontation channelled through the ruling party itself, seems to be confirmed by the state of affairs in Greece. Social discontent with the government, while clearly recorded in opinion polls, was expressed primarily through abstention, rather than by voting for one or more opposition parties.

Second, the lack of alternatives did not only make its presence felt in electoral terms — i.e. through no opposition party being electorally strong enough in the polls to threaten ND’s dominance — but also and perhaps even predominantly in political terms. The two major opposition parties, SYRIZA and PASOK, have opted for or been dragged into a consensual mode of opposition.

Despite the fact that in the last six months leading up to the elections the political discourse appeared on several occasions to be both volatile and highly polarised, as evidenced by the motion of no confidence submitted by PASOK (and supported by the rest of the opposition) or SYRIZA’s president requesting snap elections under international observation, the dividing lines between the government and the main opposition parties on multiple topics were blurry to say the least (e.g. regarding the establishment of non-state/private universities, Israel’s invasion of Palestine, Greek-Turkish relations, the role of NATO, and more generally on foreign policy).

Instead, battles between the parties, particularly in the final stretch of the campaign before the elections, were mainly focused on issues having very little to do with the key problems faced by Greek society, such as the financial records of SYRIZA president Stefanos Kasselakis. At the same time, when it comes to the smaller opposition parties — despite some of them achieving partial successes — no viable alternative capable of absorbing the disappointed voters of the three major parties was able to emerge.

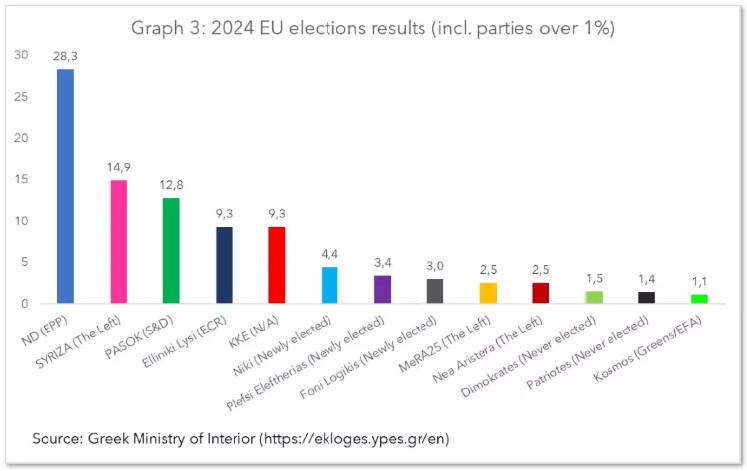

Party Results: The Balance of Terror

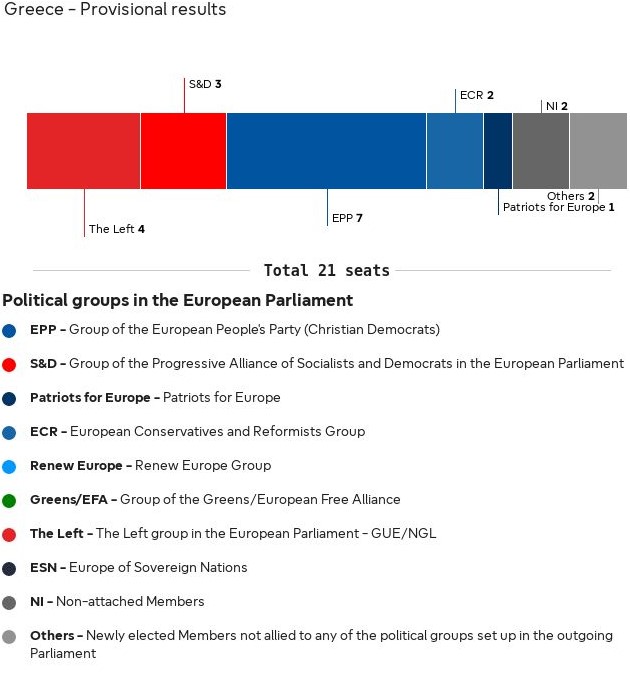

If one were to describe the dynamics of the Greek party system following the European election, they might depict it as a “balance of terror” with three components. One, a severely hurt but still (relatively) dominant mainstream right; two, an emergent and strengthened yet diverse far right; and three, a politically/ideologically vague and organisationally fragmented left. Based on the results of the individual parties (Graph 3), it appears that everyone is simultaneously both a winner and a loser.

The Mainstream Right: Hurt but Still Dominant

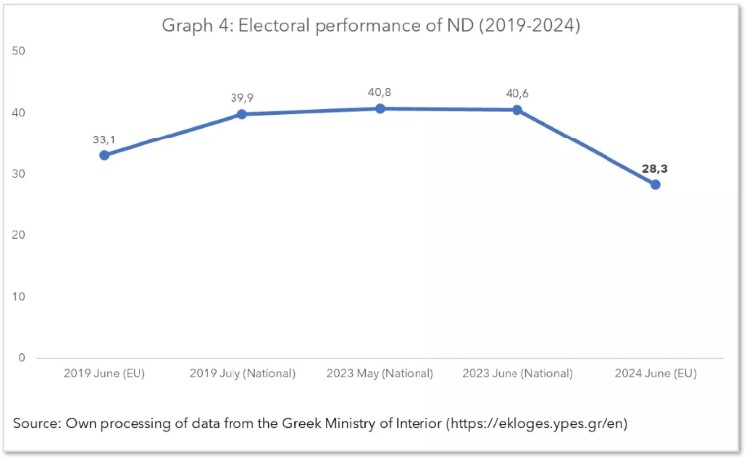

ND’s electoral result can be viewed from two very different perspectives: on the one hand, the 28.3 percent of the vote they received is far lower than the party’s performance (40.6 percent) in the most recent national elections in June 2023. It is also significantly lower than the party’s performance at the 2019 European elections (33.1 percent), which was expressly set as this year’s electoral goal by the PM, Kyriakos Mitsotakis (Graph 4).

On the other hand, ND still won almost twice as many votes as SYRIZA, and its overall performance is still higher than the joint electoral performance of its two major opponents (SYRIZA and PASOK), who received 27.7 percent of the vote combined. In spite of this, many analysts and politicians may see the recent result as a sign of the beginning of the end of Mitsotakis’s absolute dominance both nationally and within his party.

In any case, it is clear that regardless of public statements, the PM did not interpret this result as a victory, and explains why one of his first post-election initiatives was a government reshuffle, albeit one of limited depth. For the ruling party, the potential end of its unquestionable dominance at the national level is likely to fuel internal disputes between its traditional factions and its more centrifugal tendencies, especially if the far-right bloc manages to unite and become more dynamic.

All Shades of Black: A Strong and Diverse Far Right

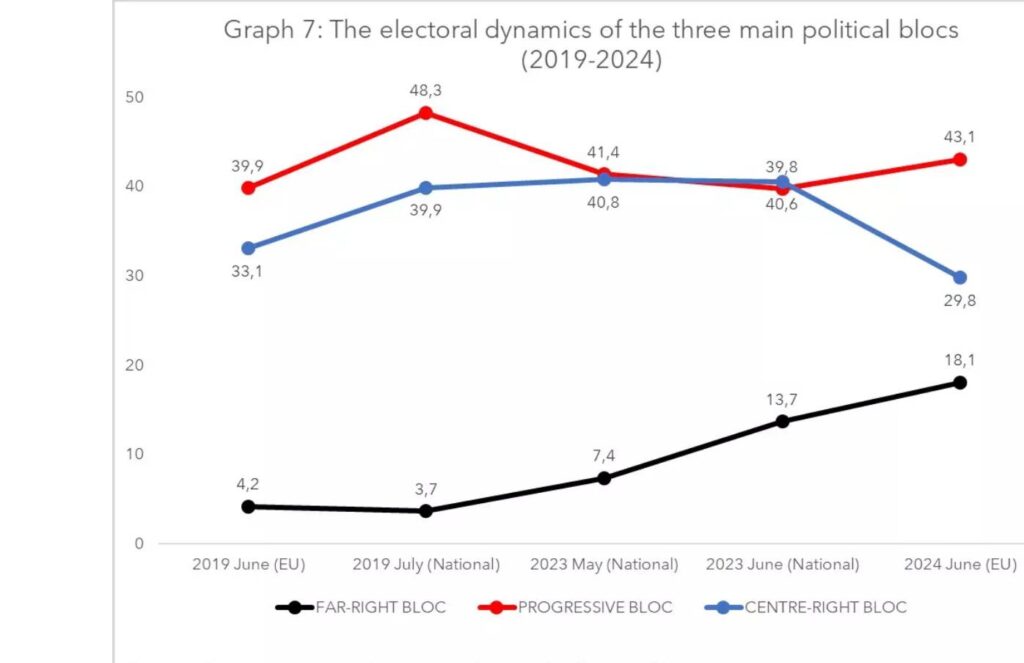

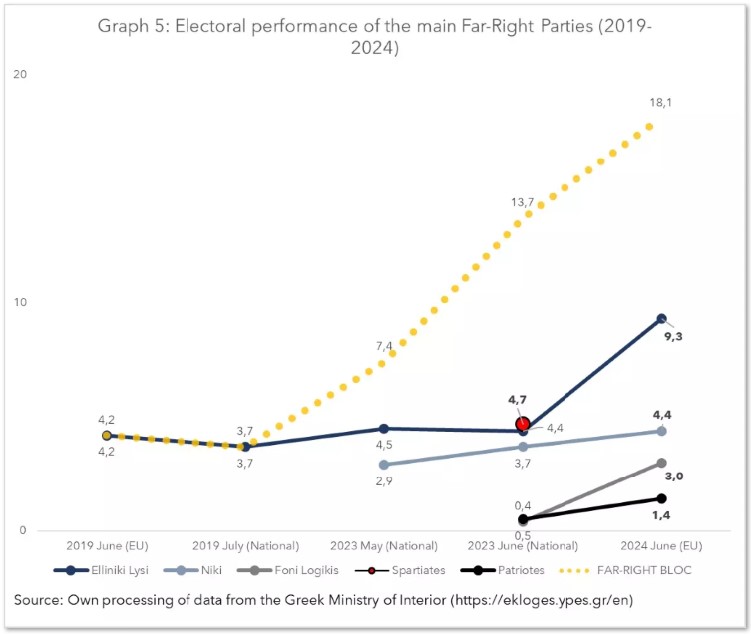

In terms of political blocs, it is undoubtedly the far right who are the big winners of the European elections in Greece, and have in fact been experiencing a steep upward trajectory since 2019 (Graph 5). First of all, in terms of vote share, the far-right parties jointly secured more than 18 percent, being one of the main beneficiaries of social discontent, especially that which is aimed at the ND government.

According to joint exit-poll data,2 ND lost more than 12 percent of its June 2023 electorate share to the far-right parties. This shift of a conservative electorate towards more radical (far-)right options also had a regional dimension: the far-right parties, particularly Elliniki Lysi and Niki, had their best results in northern Greece, a traditionally more conservative area with strong nationalist and religious sentiment.3

What is also interesting and rather unique in a European context is that Greece currently has three distinct successful far-right projects, not only in terms of electoral performance but also in terms of their ability to gain representation at the EP level, with a number of additional far-right parties and organisations also in the mix. We will now explore this in more detail.

Currently, the strongest far-right party is Elliniki Lysi (“Greek Solution”), led by Kyriakos Velopoulos, who became famous from his telemarketing shows. Elliniki Lysi is an ultra-conservative, traditionalist party that makes frequent references to Greek Orthodox Christianity, pro-Putin rhetoric, and conspiracy theories. In the post-memoranda era, Elliniki Lysi has appeared the most stable party of the far-right bloc. It was also a clear winner of the EU elections, managing to double its share of the vote.

The second party of the far right is Niki (“Victory”), which could be described as “the party of the Greek Orthodox church”, or at least of a part of it. Its anti-feminist/anti-abortion and anti-LGBTQI positions have made it a rather obvious choice for ultra-conservative voters dissatisfied with Kyriakos Mitsotakis due to his decision to introduce laws concerning same-sex marriage and adoption by same-sex couples. Although Niki was established relatively recently (running for the first time in the May 2023 national elections), for the moment it appears rather stable and managed to secure a seat in the European Parliament, despite the fierce competition evident within the far-right bloc.

The far-right bloc is diverse in nature, consisting of almost all of the different categories of far-right parties known to academia and ranging from overtly neo-Nazi organisations to those that pursue neo-conservative approaches.

The third far-right party that entered the EP and was one of the big surprises of these elections, managing to multiply its electoral share seven-fold, is Foni Logikis (“Voice of Reason”). Party leader Afroditi Latinopoulou is a young woman who has captured public attention on multiple occasions with her hate-filled comments, particularly those directed against migrants and the LGBTQI community. She openly identifies herself with Giorgia Meloni and the European Conservatives and Reformists group, and prioritises anti-immigration policies, border control, and “family values”, while at the same time supporting economic liberalism and advocating for lower taxes and market deregulation of the market as a means to incentivise private investment.

Lastly, there is also a fourth party that managed to gain more than one percent of the vote. Patriotes (“Patriots”), led by Prodromos Emfietzoglou, is considered more extreme than the three other noteworthy parties of the far right and is considered to be one of the main recipients of neo-Nazi votes following the Greek Supreme Court’s decision to ban Spartiates (“Spartans”), the successor to the neo-Nazi party Xrysi Avgi (“Golden Dawn”), from running in the European elections. According to the joint exit poll findings, a large number of former Spartiates voters opted for Patriotes, which won over 30 percent of these voters, as well as Elliniki Lysi, which received 25 percent of them. In contrast, Niki and Foni Logikis appear to have a different electoral base, as they received only 10 and 8 percent of Spartiates’ former voters.

The far-right bloc is diverse in nature, consisting of almost all of the different categories of far-right parties known to academia and ranging from overtly neo-Nazi organisations to those that pursue neo-conservative approaches. For the moment, the far-right bloc remains fragmented, which has fortunately prevented it from playing a more significant and impactful role.

This situation may not persist, however, as calls have already been made to unify the conservative or “patriotic” political space. Any potential leader will play a decisive role should this come to pass. As things stand, Kyriakos Velopoulos is the strongest party leader on this side of the political spectrum, but Afroditi Latinopoulou has also made significant gains, leaving many people wondering whether we are witnessing the rise of a new Giorgia Meloni.

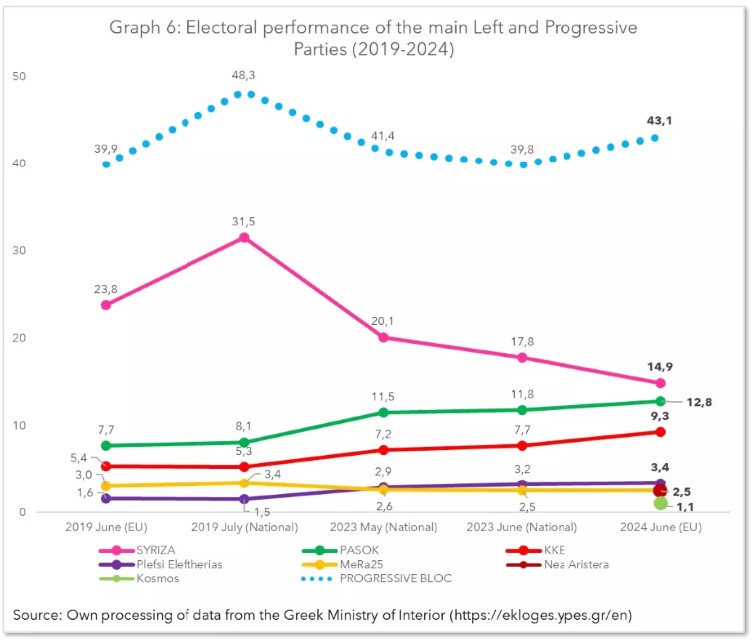

The Left Bloc: A Vague and Fragmented Space

Although the results of the parties that make up the left and progressive bloc were expected, they still represent a negative outcome. The two major forces of the centre-left, SYRIZA and PASOK, failed to achieve their electoral goals, with SYRIZA’s vote share further shrinking and PASOK achieving only limited gains. And although SYRIZA has maintained its position as the biggest party in the left-wing family, the two parties are now actually almost equally strong, thus leaving the “centre-left civil war” wide open and without a clear winner.

In contrast, the Communist Party of Greece is one of the European election’s clear winners, continuing its upward trajectory. Most importantly, KKE is particularly strong — in third place and sometimes very close to SYRIZA — in almost all urban areas of Attica (i.e. the metropolitan region of Athens), particularly in the popular/working-class districts, such as in western Athens, where KKE won 15 percent compared to the 19 percent achieved by SYRIZA; the second district of Piraeus, where KKE got 14 percent of the vote compared to the 18 percent secured by SYRIZA; and the western district of Attica, where KKE received 12 percent compared to SYRIZA’s 14 percent.

In terms of the smaller parties among the progressive bloc, the three parties that were on the verge of securing a seat in the European Parliament according to the pre-electoral polls (i.e. Nea Aristera (“New Left”), MeRA25, and Kosmos (“The World”)) all failed to reach the three percent threshold. The extremely quiet — and practically non-existent — campaign period and the absence of an actual public debate concerning the major challenges facing Greece and the EU meant that these parties did not have the opportunity to make themselves visible to voters.

Finally, there is one party that deserves further in-depth examination: Plefsi Eleftherias (“Course of Freedom”). With an ambiguous political identity, though drawn largely from the left (the party’s leader, Zoi Konstantopoulou, was parliament speaker during the first SYRIZA government from February–October 2015), the party denies the existence of a division between Left and Right, adopting left-wing and progressive positions on some matters, such as socioeconomic questions or LGBTQI issues, but rather conservative ones on other matters, especially with regards to foreign policy. This ambiguity is also reflected in the party’s electorate, since (according to the joint exit poll) the party scored its best result among those who refuse to place themselves on a left-right axis (7 percent) followed by those who identify as centre-leftists (6 percent). Despite this ambiguity and the fact that the party is almost exclusively built around its leader’s personality, for the moment it is stable and slowly growing.

Moving away from the results of each party and examining the overall state that the Left and progressive bloc finds itself in, one notices that although it still remains the biggest bloc in the Greek political sphere, managing to win 43 percent of the popular vote (thus slightly increasing its electoral impact), at the same time it is also the one mired in the more severe crisis (Graph 6). There are three main reasons for this.

First, the progressive political space is extremely fragmented. In the European elections, it consisted of seven relevant parties (i.e. those capable of winning more than one percent of the vote). As one might expect, this poly-fragmentation hinders inter-party dialogue and common action while also depriving the progressive bloc of having any majority potential in the eyes of voters.

This situation on the supply (parties’) side is quite the opposite of what can be seen on the demand (voters’) side.

It is characteristic of this fragmentation that in a post-electoral poll by “Opinion Poll” for the news website libre.gr, 72 percent of respondents, including 47 percent of 2024 SYRIZA voters and 72 percent of 2024 PASOK voters, agreed with the following statement: “Given the political balance of power, no party of the centre-left under its current leadership can achieve victory over ND and Kyriakos Mitsotakis in the next national elections in three years’ time unless something changes”. Another factor that contributes to the sense that there is no prospect of the progressive bloc holding a majority is the internal disputes between the parties that comprise it: the Communist Party of Greece steadily refuses any discussion and common action with the rest of the bloc, while SYRIZA’s current leader has chosen the rather conservative Plefsi Eleftherias as the party’s preferred ally and rejects any dialogue with the splinter party of Nea Aristera and to a lesser extent PASOK.

Second, the aforementioned fragmentation is not only organisational but also political and ideological in nature, creating a political space that is not only diverse but also rather vague. The progressive bloc includes all kinds of parties, from examples of the new “conservative left” such as Plefsi Eleftherias to moderate Europeanist Green organisations such as Kosmos, along with versions of the social-democratic, radical, and Communist left, all of whom actually have very little in common in ideological and programmatic terms.

This vagueness (i.e. absence of a clear and coherent discourse) is caused by the lack of a real and in-depth ideological and programmatic debate both between as well as within the respective parties, along with the hegemonic dominance enjoyed by the economically liberal and socially conservative ideas espoused by the ruling party, which has also impacted the progressive bloc, and particularly SYRIZA, as explained both above and in more detail in our pre-electoral analysis.

Third, the progressive bloc’s current crisis is to a large extent connected to the electoral decline, political vagueness, and persistent internal turmoil in the bloc’s biggest component, SYRIZA, which has continued to play out following the European elections.

The current impasse facing the progressive bloc is related to the lack of a dominant party on the left of the political spectrum. Although PASOK ultimately failed to capture second place from SYRIZA, the two parties are almost equally strong at present, meaning that there remains no clear winner of Greece’s left-wing civil war who could set the tone for the future of the bloc and seize the initiative. At the same time, the fact that SYRIZA has not yet managed to solidify its political, ideological, and programmatic identity under its new leadership and following its recent split makes the search for common ground with the rest of the bloc’s parties even more difficult, due to the constantly shifting landscape it has produced.

This situation on the supply (parties’) side is quite the opposite of what can be seen on the demand (voters’) side. In the aforementioned post-electoral poll, 58 percent of respondents, including 80 percent of 2024 SYRIZA voters and 74 percent of 2024 PASOK voters, agreed with the statement that “The convergence and joint action of the centre-left forces (e.g., SYRIZA, PASOK, Nea Aristera) would be a positive development for the country’s political life and would make the centre-left a serious contender against ND and Kyriakos Mitsotakis”.

In addition, 46 percent of respondents, including 48 percent of 2024 SYRIZA voters and 54 percent of 2024 PASOK voters, reacted positively to the prospect not only of joint action by centre-left forces but of the founding of a new unitary centre-left party. This is similar to the findings of the recent Metron Analysis survey, according to which 70 percent of respondents, including 83 percent of 2024 SYRIZA voters, 83 percent of 2024 PASOK voters, and 75 percent of 2024 KKE voters, support the convergence of the centre-left forces in a new unitary formation, with 27 percent in favour of the existing structures being maintained.

The extent to which this pressure from the electoral base will have a real impact on the parties’ strategies remains unclear. What is certain is that internal developments within the respective parties — in particular the way in which the ongoing crisis in SYRIZA is resolved along with the outcome of PASOK’s upcoming leadership election — will play a decisive role.

The Political Landscape after the EU Elections:

Continuity or Rupture?

As we pointed out at the beginning of this analysis, the recent European elections signify both continuity and rupture of the existing political landscape in Greece, inaugurating a transitional period for the country’s party and wider political system.

In terms of the individual parties, the idea of a continuation of pre-electoral dynamics seems to be of increased relevance. Although wounded, the ruling party is still and by far the strongest one. Given the fact that in national elections, the law also favours the first party, it is clear that if nothing changes drastically, ND will retain a clear lead over other parties. In addition, the ongoing crisis of the two major centre-left parties means that they do not pose an imminent threat to ND’s dominance, and nor does the emergent but still fragmented and weak far-right.

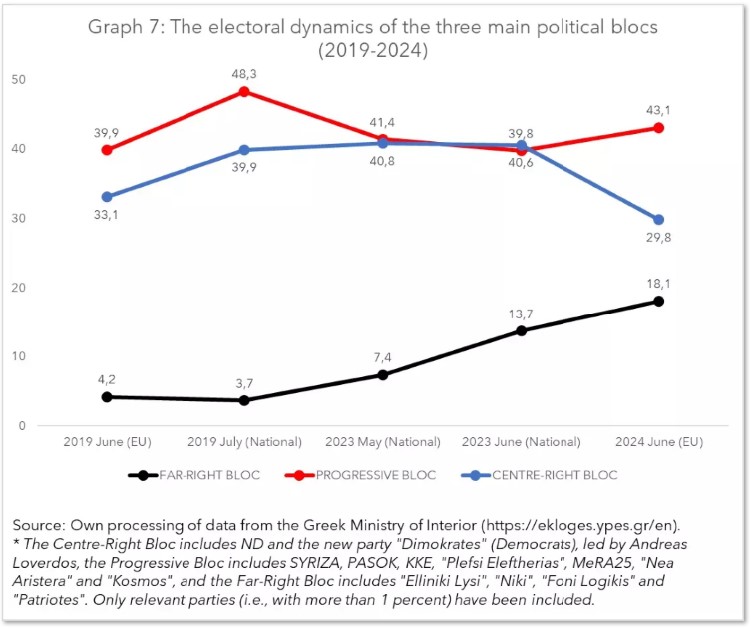

However, a more careful look at the results that adopts a broader approach that focuses not on specific parties but on wider political blocs points to a rupture in the prior political landscape (Graph 7). The dominance of the centre-right/liberal bloc seems to be coming to an end. The progressive bloc has regained and broadened its (relative) majority against the centre-right bloc, which is at the same time threatened by the rise of the far-right.

This new balance of power is extremely fragile. First, the blocs exist only as analytical frameworks, given that — at least for the time being — both the progressive and the far-right bloc remain fragmented in real political terms. Consequently, their position and their dynamics will depend on the internal reconfiguration of each bloc. Second, the centre-right/liberal bloc will feel even more pressure from its more conservative/radical electorate from before; as a result, Kyriakos Mitsotakis will have less room for the kind of political manoeuvres that previously allowed him to win over a large part of the centrist/liberal electorate.

In the medium- and long-term, one can predict three different outcomes from this fragile balance of power. First, if neither the progressive nor the far-right bloc manage to successfully reconfigure and unite, the ruling party will continue to dominate, although with less ease than before. Second, a unified progressive or a unified far-right bloc could create a social and political dynamic that will seriously question ND’s dominance and produce a new majority. Third, if tripartism becomes solidified, the big question would be where the centre-right/liberal bloc lean would towards, i.e. whether it will choose to form a democratic alliance with the progressive bloc against the threat of the far-right or — as it is the case in many European countries at the moment — it will choose instead to collaborate with the far-right.

Lastly, there is also a fourth scenario. As identified above, the blocs are far from internally coherent, while at the same time the respective parties are far from ideologically and politically unified or stable. Changes inside the existing parties continue to evolve — such as the ongoing transformation of SYRIZA or the possible revival of ND’s internal fragmentation — and this may have a significant impact, causing a broader reconfiguration that would liquidate existing party structures, transcend the above-described blocs, and generate totally new — and currently unpredictable and seemingly odd — alliances.

This paper was originally published on the website of the Rosa-Luxemburg foundation.

References

1 Two national elections were held in May and June 2023 respectively, as well as two rounds of local and regional elections in October 2023.

2 The joint exit poll was conducted on the day of the election by 6 major Greek polling companies (Metron Analysis, Alco, Marc, MRB, GPO, Pulse) at a sample of 90 polling station and 5.672 voters.

3 In several electoral districts in Central Macedonia, Elliniki Lysi even managed to achieve second place, securing more than 18 percent of the vote.