Despite the victory of the centre-left PS, the results of the 2024 European elections confirm a shift to the right in Portuguese politics and the retreat of the radical left. However, the nice surprise of election night was the poor performance of the far-right Chega, just three months after its meteoric rise.

Source: Verian for the European Parliament

https://results.elections.europa.eu/en/national-results/france/2024-2029/

Results and Turnout

The election to the European Parliament (EP) saw a notable increase in voter turnout, rising from 31% in 2019 to 37% in 2024, alongside a reduction in blank and null votes from 7% to 2%. Several factors may explain this:

- The proximity to the 2024 general election on March 10 likely had a spillover effect on participation;

- The perceived greater importance of these elections, possibly due to the war in Ukraine and the rise of the far right in Europe and Portugal;

- A broader political offering, with new viable parties on both the left and the right, such as Chega, IL, or Livre;

- And perhaps most importantly, the introduction of mobile voting, which allowed citizens to vote at any polling station thanks to digital electoral rolls.

However, turnout was still well below the 60% recorded in the March 10 national election.

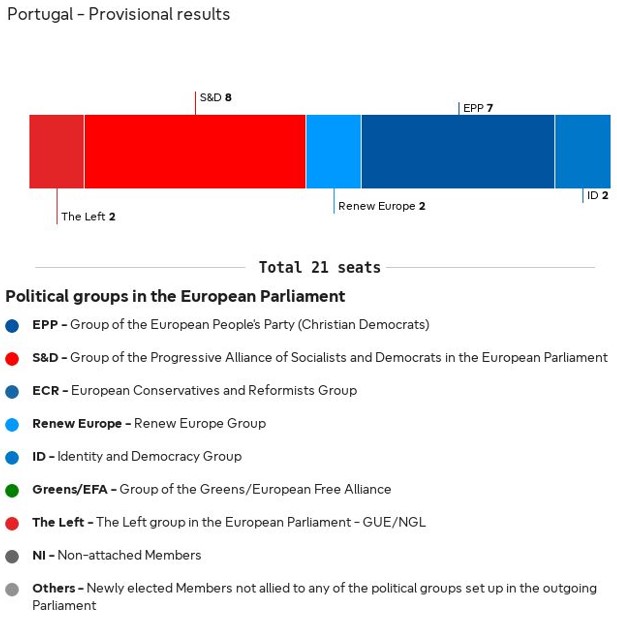

The results gave victory to the centre-left PS (S&D) with 32.1% of the vote and 8 MEPs. Despite losing one seat compared to 2019, this result represents an increase of 4.1 percentage points from 28.0% since the March elections. The Democratic Alliance (AD) coalition, made up of the centre-right Social Democratic Party (PSD) and the conservative CDS/PP, both members of the EPP and currently in government, came second, slightly increasing their share from 28.8% to 31.1%, maintaining 7 MEPs (6 for PSD and 1 for CDS/PP).

The other two right-wing parties followed. Chega (ID) won 9.8% of the vote, and the Liberal Initiative (IL, Renew Europe) 9.1%, both securing representation in the European Parliament for the first time, with 2 MEPs each. The radical left failed to win back voters, maintaining their March support, with the Left Bloc (BE, The Left) on 4.3% and the communist-led Unitary Democratic Coalition (CDU, The Left) on 4.1%, each with just 1 MEP. Finally, the European Greens lost their only Portuguese MEP, with Livre (3.8%) and People-Animals-Nature (PAN) (1.2%) failing to win any seats.

A Brief Analysis

These elections did not exhibit the typical characteristics of second-order elections. There was no punishment of mainstream or governing parties, nor a major boost for challenger parties (except IL) compared to the general elections. This is likely because there wasn’t enough time for voters’ preferences to shift significantly. Consequently, these elections were viewed more as a second round of the March elections, confirming the rightward shift and growing fragmentation of the Portuguese party system.

Interestingly, the two mainstream parties slightly improved their results compared to the general elections. However, this result masks the consolidation of historically low support for the two parties that have dominated Portuguese politics since 1974. The PS celebrated a symbolic victory but did not secure enough votes to aspire to return to power soon. The AD did not grow as much as expected, showing no signs of a solid majority in parliament in hypothetical early elections. Notably, the centre-right coalition, led by Sebastião Bugalho, resisted adopting anti-immigration rhetoric during the campaign, distancing itself from harsher positions within the EPP and suggesting “improvements” to the Asylum Migration Pact. This indicates no significant contamination of the centre-right by the far-right, at least for now, as seen in other countries.

For Chega, 9.8% was a very disappointing result after the 18.1% obtained in the general election. Despite immigration being a very salient issue in the campaign – perhaps for the first time in Portugal – several reasons have been suggested for this poor performance. These include the weak performance of its top candidate, Tânger Corrêa, which forced party leader André Ventura to take a more prominent role in the campaign. Additionally, the party struggled to mobilise part of the new electorate it had attracted from abstentionists in the general elections. Finally, the possibility of losing voters to AD, and in turn, AD losing voters to IL, could also have affected its performance. Conversely, IL’s 9.1% and two MEPs positioned the party as the main winner of the night. IL appears to have benefited from a strong candidate, former party leader João Cotrim de Figueiredo, who delivered compelling debate performances. Furthermore, IL capitalised on a lack of pressure for the strategic vote, which led part of its potential electorate to vote for AD in March.

The radical left spoke of “resistance” in maintaining its representation in the EP, though it received its lowest combined share of the vote since Portugal joined the EU (8.4%). This is particularly concerning given that BE and CDU fielded strong candidates. Despite former leader Catarina Martins’ strong performance in debates, BE struggled to win back progressive and young voters, who seemed to favour Livre and even IL. João Oliveira (CDU) managed to secure EP representation despite struggling with the Ukraine issue – a challenge the party has faced for the past two years – benefiting from a loyal electorate in an election with lower turnout than legislative elections.

The two Green parties failed to win any seats, with Livre’s performance being particularly disappointing despite some polls suggesting it could elect two MEPs. The party’s controversial primaries and (apparent) lack of unity during the campaign seemed to cost it a better result. After being the big surprise of 2019, PAN continues its downward trajectory, securing its lowest result in a nationwide election since 2011.

The Campaign

The campaign began late, with the new Portuguese government taking office in early April, and candidates from the two largest parties announced just six weeks before the EP elections.

The campaign unfolded in two distinct phases. Initially, a series of televised debates featured four candidates each. The notable surprise was the prominence of European issues, diverging from the typical focus on national concerns that usually characterises EP elections in Portugal. Migration, the war in Ukraine, and European defence policy emerged as particularly significant topics, despite only 8% of Portuguese identifying migration as a top concern – a figure well below the EU average of 24%. Surprisingly, environmental issues and the climate transition received relatively little attention from the parties and the media, despite being the central theme in the 2019 EP campaign.

The second phase, the official campaign period, saw national political issues take centre stage in the political discourse and media coverage. This shift was bolstered by the new AD government’s launch of a series of measures perceived as potentially popular, such as the new Health Emergency and Transformation Plan, an Action Plan on Migration, and the “Building Portugal” plan with a new liberal housing strategy. Unexpectedly, the final days of the campaign were overshadowed by judicial raids on the Ministry of Health premises, allegedly involving two former PS cabinet members playing a role in facilitating access to an expensive treatment in a public hospital. However, apart from Chega, most candidates refrained from exploiting the case for campaign purposes.

Implications

These results will directly influence the main issue in Portuguese politics in the months ahead: the approval of the 2025 state budget and the survival of the current AD government. Paradoxically, they put pressure on its two main opponents, the PS and Chega, to prolong the minority government’s tenure.

While the results were seen as a victory for the PS and its new leader, Pedro Nuno Santos, the party cannot realistically aim to form a government even with potential leftist support (BE, PCP, and Livre). This leaves the PS in a difficult position: either making AD’s 2025 budget viable or facing elections with limited prospects for growth. There are voices within PS advocating abstention in the autumn budget vote. Similarly, Chega, reeling from an unexpected electoral setback, will be cautious about precipitating the fall of a right-wing government and risking a significant reduction in the public subsidies the party currently enjoys.

For the radical left, the continued losses align with broader trends in European countries, likely leading BE and PCP into introspection. Many argue the two parties have struggled to take credit for popular measures from the Geringonça experiment (2015-2019) and will need to reassess their strategies. The PCP faces speculation about its survival, while remaining central to the relatively weak Portuguese trade union movement. BE must contend with competition from new political forces and the challenge of appealing to both old and new voters. The current landscape requires new solutions beyond the anti-austerity platform that brought them success in the 2010s, as the fight against the far right alone has proven insufficient to motivate voters.

Cover photo: A meeting of former MEPs Catarina Martins (speaking, reelected) & Marisa Matias with neighbourhood residents inn Quinta Da Lage, Amadora, Portugal (2019). Source: Esquerda.net Flickr account (CC-BY-SA).